Louisa Twining 1820 – 1912

Philanthropist, artist, reformist.

16 November 1820 – 25 September 1912

Louisa Twining: A tribute by Kathleen McCrone

Louisa Twining, of the famous tea family, was a longtime Bloomsbury resident (1836-1882). Deeply involved in the area’s life and in numerous philanthropic activities, she became nationally known as the originator of workhouse reform and for doing more than anyone else to improve the standards of Poor Law administration.

Background, Bloomsbury and Artist

Louisa was raised in a sheltered household in Norfolk Street, the Strand near the family business. Educated at home by her mother and sisters and by art and languages tutors, her lack of formal schooling was compensated for by foreign travel and the scholarly and cultural influences of her upper-middle-class family. Particularly influential were ‘delightful and instructive’* lectures on science subjects at the Royal Institution, where she listened to the renowned physicist Michael Faraday, and on moral philosophy at Queen’s College, Harley Street, by its founder, the theologian and Christian socialist Frederick Denison Maurice.

In 1836 when Louisa was 16 the Twining family moved to more salubrious Bloomsbury, settling at 13 Bedford Place, Russell Square. She received a liberating inheritance of £17,000 after her parents’ death and in 1866 relocated to a ‘charming, spacious mansion of Queen Anne date’ at close-by 20 Queen Square. She lived there until 1882.

A talented artist, as a younger woman Louisa’s primary interests were painting and art history, a subject explored during 135 (by her own count!) ‘delightful’ visits to the nearby British Museum. She published two impressive art history books: Symbols and Emblems of Mediaeval Christian Art (1852; 2nd ed. 1885) and Types and Figures of the Bible (1855).

The Reformer

However, in her thirties, Twining, a deeply committed Christian, changed her focus to alleviating poverty. In 1847 she began home visits to the poor, and by the early 1850s, was also involved in F. D. Maurice’s efforts to help needlewomen at what became his Working Men’s College first at 31 Red Lion Square and then from 1857 45 Great Ormond Street. However, the defining moment came in 1853, when she visited her first workhouse–the Strand Union in Cleveland Street. She was so shocked that charitable work took over her life. Other workhouse visits followed, such as to the dreadful St. Giles Union Workhouse, Holborn in 1856. Reforming the Poor Laws, and improving the appallingly degrading and deprived living conditions and ‘tyrannical’ treatment of workhouse inmates, became Twining’s mission.

Improvement could only happen with outside visits from witnesses. This idea was at first met with resistance by the men who controlled these institutions and considered reforming women like Twining as nuisances and threats to discipline and male authority. Twining responded by developing the public’s consciousness about what was going on through publicity. She shifted her literary skills from art history to writing pamphlets and journal and magazine articles. Twining also wrote to newspapers, petitioned the Poor Law authorities and gave lectures around the country. She called for the separation of sick, old and able-bodied inmates and staff medical training, and for systematic workhouse visiting by middle-class ladies.

Her first pamphlet, ‘A Few Words about the Inmates of our Union Workhouses’, was published in 1855. In 1857 came a string of letters to The Guardian and an influential paper ‘On the Condition of Workhouses’, at the inaugural congress of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science (NAPSS). Twining urged the establishment of a workhouse visiting society, which would enlighten public opinion and introduce a voluntary system of workhouse visiting intended to improve inmates’ lives and bring them moral and spiritual comfort.

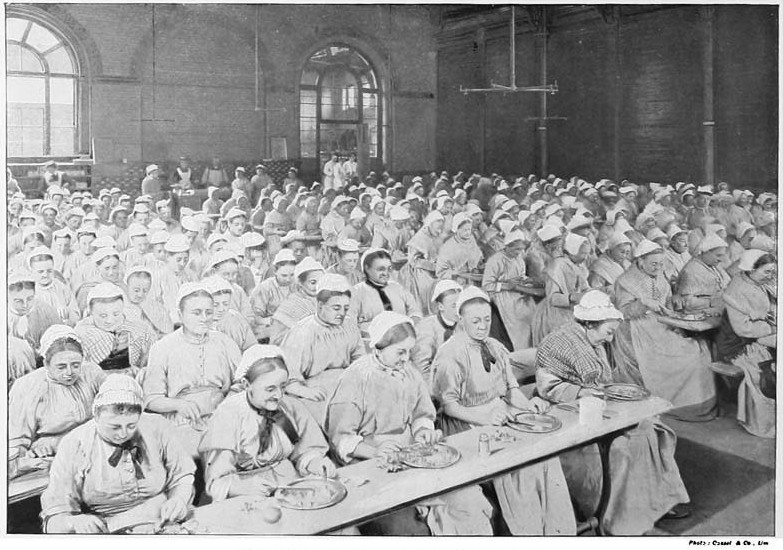

Dinner-time in St Pancras Workhouse between 1897-1899 Various authors for Cassell & Co., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Poor Law Board yielded and a Workhouse Visiting Society (WVS) was established in affiliation with the NAPSS, with Twining as its honorary secretary and journal editor. The WVS made the first successful attempts to organise systematic workhouse visiting and to awaken public interest in poor relief and workhouse conditions.

In 1861, under the aegis of the WVS and supported by the fabulously wealthy Angela Burdett-Coutts, Twining opened an Industrial Home for the Instruction of Workhouse Girls sent out to service, at 23 New Ormond Steet (now 22 Great Ormond). Next door she also established a Home for Aged and Incurable Women who would otherwise be homeless. As lady superintendent, Twining handled both Homes’ ‘arrangements and business…as well as the management of…funds.’ Oversubscription was immediate, which led Twining, in 1866, to establish and manage St. Luke’s Home for Epileptic and Infirm Women in her own Queen Square residence. She also helped improve the quality of workhouse nursing collaborating with others, including Florence Nightingale. The aim was to train and attract better-educated women as workhouse nurses and matrons. In 1879, Twining became honorary secretary and vice-president of the Association for Promoting Trained Nursing in Workhouse Infirmaries and Sick Asylums.

Added to this workload, Twining pursued a staggering number of other social causes. This included the opening of Lincoln’s Inn Fields to the public. She joined a Universities Mission to Central Africa, helped to form a Ladies’ Diocesan Association, attended Ladies’ Sanitary Association lectures and raised money to establish a refuge for East End cholera patients. Twining campaigned for prison reform and supported the clearing out of the Bloomsbury slum Little Ormond Yard. She acted as superintendent of a Parochial Mission Women’s Society, supervised a mission house and working men’s club, served on the councils of the Provident Medical Association and the Metropolitan and National Nursing Association, 23 Bloomsbury Square, and assisted those newly released from asylums and prisons. At the Parish of St. George the Martyr, Queen Square she worked with members of the temperance movement and at mothers’ meetings; and together with Angela Burdett-Coutts she founded an art students’ home at 4-5 Brunswick Square (1879). In addition, she continued to visit workhouses regularly to give papers at national meetings and to write to and meet with government officials about her favourite philanthropic subjects.

Twining regarded all this voluntary work as a great privilege. However, in 1882, age 61 and worn out, she resolved to retire, and sought rest in a year’s European travel. This ended Louisa Twining’s direct connections withBloomsbury but not with social reform. She had another 30 years to live and remained a force to be reckoned with.

The Feminist

Twining was a committed feminist, who supported all the ‘great movements’ for women’s rights. While continuing to respect women’s traditional domestic role, Twining believed that women should play useful roles outside the home. She joined the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women only two years after its foundation in 1859. Although not active in the organisation she made clear in her charitable work that she favoured expanding the number of respectable occupations available to self-supporting middle-class women, and for years she advocated the recruitment of qualified women to managerial positions under the Poor Law, as matrons, superintendents, inspectors and elected guardians. (As the chief financial supporter of a Society for Promoting the Return of Women as Poor Law Guardians (1881), she sat on its council and chaired its executive.) Recognising that education and employment were synonymous, Twining felt that middle-class girls needed training for professional work and serious academic education. Higher education she also considered a necessity, lauding as ‘epoch-making’ the establishment of ladies’ colleges at Oxford and Cambridge.

As for the key feminist issue–the vote, Twining belonged to the National Society for Women’s Suffrage (1867), for many years supporting women’s enfranchisement in local government elections, i.e. for town and country councils and school and poor law boards, and most importantly for Parliament itself, on the same terms as men. She did so because these bodies dealt with many social questions to which women’s informed input would assure more effective responses. In 1904, age 84, she even accepted election as President of the Women’s Local Government Society, which promoted women’s eligibility to vote for and serve on all local government bodies.

Twining, was a progressive conservative. She did not believe that men and women were or should be completely equal. While she wanted reformers of both sexes to collaborate in a ‘communion of labour’, she felt they should do so in separate spheres because their talents were different and complementary. She also doubted women’s physical strength, fearing the results of the ‘excessive increase’ in girls’ athletic pursuits such as bicycling.

Despite these conservative gender views, Twining deserves recognition as a major feminist pioneer and as a role model for other women. She was fully aware that the example of successful women like herself gave confidence to other women, and contributed to a redefinition of women’s rights and abilities. In her outstanding career as philanthropist and reformer, Twining proved that women could be effective instruments of social reform and that they deserved equal citizens’ rights.

Death and Legacy

Louisa Twining died of bronchitis in Kensington on 25 September 1912. She was almost 92 and had lived to see implemented many of the Poor Law advancements for which she had worked so hard. The Times obituarylauded her 50 years of ‘improving’ work and agreed that it was ‘not too much to say that [she had] raised the whole tone and standard of Poor Law administration through the country.’

*Except for titles and the above quotation from The Times, words in quotation marks come from Twining’s 1893 autobiography.

Further Reading

Banks, Olive. The Biographical Dictionary of British Feminists, Vol. One: 1880-1930. Brighton: Wheatsheaf Books Ltd., 1985.

Deane, Theresa, “Late nineteenth-century philanthropy: the case of Louisa Twining,” in Gender, Health and Welfare, edited by Anne Digby and John Stewart, 122-42. London: Routledge, 1996.

Deane, Theresa, “Old and incapable? Louisa Twining and elderly women in Victorian Britain,” in Women and Ageing in British Society Since 1500, edited by Lynn Botelho and Pat Thane, 166-85.London: Pearson Education Ltd., 2001.

Grenier, Janet E. “Louisa Twining (1820-1912),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004.

McCrone, Kathleen E. “Feminism and Philanthropy: The Case of Louisa Twining,” Canadian Historical Association Historical Papers 11, no. 1 (1976), 123-39.

“Obituary Miss Louisa Twining,” The Times, 27 September 1912, p. 7.

Parker, Julia. Women and Welfare: Ten Victorian Women in Public Social Service. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989.

Prochaska, F. K. Women and Philanthropy in 19th Century England. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980.

Twining, Louisa. Recollections of Workhouse Visiting and Management During Twenty-Five Years. London: C. Kegan Paul & Co., 1880.

Twining, Louisa. Recollections of Life and Work, Being the Autobiography of Louisa Twining. London: Edward Arnold, 1893.

Twining, Louisa, Workhouses and Pauperism and Women’s Work in the Administration of the Poor Law. London: Methuen & Co., 1898. Twining, Louisa. Papers of: National Archives; Queen’s College Library; Women’s Library, London School of Economics.

UCL Bloomsbury Project, 2007-2011.

Kathleen E. McCrone: Educated BA (Hons. History) at the University of Saskatchewan and MA, PhD New York University, she is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Windsor, in Windsor, Ontario, Canada. One of the pioneers in Canada in writing and teaching about the history of English women, she authored articles on various aspects of the history of women in Victorian England and the ground-breaking book, Sport and the Physical Emancipation of English Women, 1870-1914 (London: Routledge, 1988, reissued 2013). She also spent several years in university administration when relatively few women held senior positions.

MINI BIOGRAPHY

Education

Home educated mostly by mother and sisters, especially Elizabeth.

Attended F D Maurice’s lectures in Queen’s College, Harley Street and Bible class in Queen Square.

Supplementary Education: Tutors for art and languages; influence of father and educated brothers and notable family visitors; lectures at Royal Institution and Queen’s College, Harley St.; the London cultural environment; much domestic and European travel.

Some Key Achievements and Interests

1850s Taught classes for women in writing and needlework at F. D. Maurice’s Working Men’s College, Red Lion Square and Great Ormond Street.

1853 First workhouse visit—to Strand Union–to an elderly friend of her old nurse; was a shocking and life-transforming experience.

1853- on Took up unofficial workhouse visiting with zeal, often taking influential people with her; strongly urged Poor Law authorities, through letters, pamphlets and lectures, petitions and in-person meetings to approve organised visiting and improve conditions by separating the sick, aged and able-bodied and giving medical training to staff.

1855 First of many publications about workhouses, A Few Words about the Inmates of our Union Workhouses (Longmans).

1857 Letter to The Guardian on Homes for the Aged Poor the first of many letters to newspapers about workhouse conditions.

1857 Presented paper On the Condition of Workhouses in Birmingham to inaugural Congress of National Association for the Promotion of Social Science (NAPSS); was the first time the subject was raised in public; paper read for her because father’s death kept her in London.

1858-1859 Visited Great Ormond Street Hospital regularly to learn about nursing but recognised this was not a career path she should follow.

1858 Founded the Workhouse Visiting Society (WVS) in association with the NAPSS, having persuaded the Poor Law Board to allow women to visit workhouses regularly. Its aim was the ‘moral and spiritual improvement of workhouse inmates in England and Wales’. The WVS was successful in awakening interest in the cause. Twining was honorary secretary. In 1868 it was based at 23 New Ormond Street (now 22 Great Ormond Street).

1858-1861 and 1863 Presented in person five more papers on workhouses at NAPSS congresses

1861 Set up Industrial Home for Workhouse Girls, 23 New Ormond Street (now 22 Great Ormond Street), with considerable help from Lady Herbert and Angela Burdett-Coutt who paid the rent for three years. Girls were taught household and some nursing skills in the hope of their gaining domestic employment and staying out of workhouses. Provided a home they could return to between jobs.

1861 Gave evidence on education in pauper schools to Parliamentary Select Committee on Poor Relief, urging improvements, such as training for girls for suitable employment and appointment of women as Poor Law inspectors and guardians. Was unusual for women to appear before such committees.

1862-3 Set up Home for the Aged and Incurable, for sick and elderly women with nowhere to go but workhouse, at 22 and, from 1863-1888, 24 New Ormond Street (now 20 and 24 Great Ormond Street) with the help of Frances Power Cobbe. Nursing care partly provided by girls trained at the Industrial Home.

1865 Three meetings at Mrs. Gladstone’s house (wife of the then Chancellor of the Exchequer) about incurables in workhouses, ‘at which many influential persons were present’; example of Twining’s extensive networking and connections.

1866 Raised money for, established and visited daily a convalescent home in Lambeth for East End cholera patients.

1866 Moved from Bedford Place to 20 Queen Square, and, in her own home, established St. Luke’s Home for Epileptic and Incurable [Middle Class] Women, a group that fell through cracks ‘between pauper asylums and [expensive] private homes’; also took in a few elderly and eventually a few art students.

1867 Metropolitan Poor Act provided for ‘the entire separation of the sick poor from the other classes of inmates in [London] workhouses’, and the placement of infirmaries under separate management; both Twining goals.

1870 Set up the Workhouse Infirmary Nursing Association.

1873 First female Poor Law inspector, Mrs. Nassau Senior, appointed after much campaigning by Twining for appointment of women to this and other Poor Law positions.

1875 Women who met the required property qualification allowed to stand for election as Poor Law guardians. Twining had urged this strongly from early in her Poor Law reform work.

1879 Became honorary secretary and vice-president of new Association for Promoting Trained Nursing in Workhouse Infirmaries and Sick Asylums; first annual meeting held in Twining’s home.

1879 Set up the Home for Lady Art Students at 4-5 Brunswick Square with Angela Burdett-Coutts.

1880 Published Recollections of Workhouse Visiting and Management During Twenty-Five Years. (90 pages, plus 14 page preface and 128 pages of appendices).

1860s and 1870s Involved in a remarkable number and diversity of other charitable activities, and continued to make frequent home visits and visits to workhouses in London and around England.

1882 Worn out, she retired from her Bloomsbury activities, left Queen Square and went to Europe for a year. Had long since become a national figure.

1884-90 Elected as a Poor Law Guardian in Kensington, only second woman to become Guardian. Had support Society for Promoting the Return of Women as Poor Law Guardians for years, and been delighted when women were made eligible for election in 1875.

1885 Joined Florence Nightingale’s District Nurses Movement to send trained visiting nurses to the poor in urban areas.

188? Served on the Council of the Metropolitan and National Nursing Association, a branch of National Union of Women Workers of which she was president.

1890 Honoured at gathering of the Workhouse Infirmary Association when leaving London; presented with illuminated address signed by many she had worked with across decades.

1890-2 Moved to Worthing, where she organised district nursing.

1891, and again in 1896, Gave evidence to House of Lords Commission on Poor Law, on education of children and condition of the sick in workhouses and workhouse infirmaries.

1893-1896 Elected Tonbridge Poor Law Guardian; helped to start visiting nursing.

1904 Elected President of the Women’s Local Government Society.

1904 Honoured–Elected Lady of Grace of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem in recognition of lifetime of philanthropic work, and, for the same reason, at a gala event for her 84th birthday, close to 300 admirers presented her with an illuminated, signed address detailing her services to Poor Law improvement over half a century.

1912 17 September, last letter to The Times; lauded the achievement of Poor Law reforms she had sought since the 1850s.

Art

Was a talented artist; took art classes and believed in the elevating nature of art education; studied art history on visits to British Museum; joined new art history Arundel Society, 1849; wrote two art history books, 1852 and 1855.

Feminism

As a woman, waged constant battles to gain access for herself and other women to things open to men.

Was strongly in favour of expanding educational and job opportunities for middle-class women, of appointing women to Poor Law and other administrative positions, and of votes for women in all local government and parliamentary elections on same terms as men.

Member of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women and National Society for Women’s Suffrage.

Travel

1836-1883 Made c. 25 visits to Europe–France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Holland, Sweden, Finland, Russia, and what are now Austria, Ukraine and Czechia–often for extended periods.

1823-1900 Made innumerable visits to places all over England (saw every cathedral), and a few to Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

Issues

As a woman faced constant battles to gain access for herself and others to opportunities open to men.

Two brothers died within six months of each other.

1857 Father died; a great loss to her.

1866 Mother died. Felt this loss sorely. This represented a major break with the past.

Connection to Bloomsbury

1836-1866 Lived at 13 Bedford Place, Russell Square, Bloomsbury.

1866 – 1988 Lived at 20 Queen Square, Bloomsbury.

Many of her philanthropic and reforming activities were Bloomsbury-based.

Worshipped at St. George’s, Bloomsbury and St. George the Martyr, Queen Square.

In the 1850s, frequently visited the British Museum to study its art and insect collections.

Female Networks:

Extensive, through her connections with multiple reforming associations, institutions and churches, and with her life-long efforts to get support for her Poor Law reform work. Knew well other prominent female reformers, such as Florence Nightingale, Mary Carpenter, Frances Power Cobbe, Angela Burdett-Coutts, Octavia Hill, Anna Jameson and Florence Nightingale; and was well connected with and got invaluable support from highly placed men and women including Lady Herbert, Mrs. Tait and Lady Cecil.

Anna Brownell Jameson, Catherine Jane Wood, Florence Lees.

Some Memorable Moments

c. 1834 Heard Madame Malibran sing.

1835 First railway journey, only five years after the first such trip in Britain.

1836 Saw the aftermath of the fire that destroyed the Houses of Parliament.

1838 Saw the aftermath of the fire that destroyed the Royal Exchange.

1838 Saw the Coronation Procession of Queen Victoria from galleries set up in churchyard of St. Margaret’s, Westminster.

1840 Heard Mendelssohn play the organ at St. Peter’s Cornhill and at home of a family friend.

1840 Was read the original parts of Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby as they came out.

1840s Saw Charles Kemble and daughter Fanny act and heard Liszt play.

1851 Attended the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park.

1852 Witnessed the ‘interesting sight of the then President, Louis Napoleon’s, entry to Paris’.

Heard some of the great Divines of the age preach, i.e. Wilberforce.

Writing/Publications include:

By her own count (1898), her publications on matters of poor law administration 1855-1894 numbered 41. Her lifetime total number of her publications is higher.

Many letters to The Guardian, The Times and other newspapers, numerous pamphlets, journal articles and addresses and five books.

1852 Symbols and Emblems of Early and Mediaeval Christian Art.

1855 The Types and Figures of the Bible.

1857 Pamphlet Metropolitan Workhouses and their Inmates. (Longmans).

1858 The Times published her letter on Workhouse Nurses.

1858 Pamphlet Workhouses and Women’s Work (Longmans), reprinted from Church of England Monthly Review (1857).

1880 Recollections of Workhouse Visiting and Management During Twenty-Five Years

1893 Published Recollections of Life and Work: Being the Autobiography of Louisa Twining. (291 pages, written in 4 months).

1898 Published Workhouses and Pauperism and Women’s Work in the Administration of the Poor Law. (276 pages).

Gave works of art by herself and others to the Working Men’s College, Kings College and to several galleries and other institutions.

with thanks to Kathleen McCrone

Further reading

Women, the Workhouse and Victorian Philanthropy | University of London

The Times/1912/Obituary/Louisa Twining – Wikisource, the free online library