Emily Davies 1830 – 1921

(Sarah Emily Davies)

Suffragist, education activist.

22 April 1830 – 13 July 1921

Emily Davies: A tribute by Gillian Murphy

Emily Davies is a relatively unknown Victorian. Yet she was at the heart of political, educational, journalistic and social reform movements of her time. What we know about Davies is through a ‘Family Chronicle’, held at Girton College Cambridge, which she wrote for her nephews and nieces. There are also Davies’ surviving letters, spread across several repositories and her published writings. This blog highlights Davies’ work when she lived in London.

Early years

Sarah Emily Davies was born in Southampton in 1830, the fourth child and second daughter of five siblings. Her father was the Reverend John Davies who had recently moved his boarding school from Chichester to Southampton. The family moved several times until Reverend Davies accepted a parish in Gateshead in the north of England.

Davies struck up a lifelong friendship with Jane Crow. The Crow sisters had been educated at Blackheath School in south London where Elizabeth Garrett had also been educated. In 1848, when Davies was 18, the Crow family moved to Gateshead. Through them Davies met Garrett when they were bridesmaids at Annie Crow’s wedding in 1854. Davies and Garrett remained close friends all of their lives.

The London Years

When Reverend Davies died in October 1861, Emily and her mother had to leave the rectory in Gateshead. They moved to 17 Cunningham Place in St John’s Wood in north-west London, which was close to her brother Llewelyn Davies and to the home of Barbara Bodichon. Davies first met Bodichon in Algiers when Emily was nursing her brother, Henry. Bodichon was a member of a progressive Unitarian family, had founded the English Woman’s Journal in 1858 with Bessie Rayner Parkes and was a leading member of the Langham Place Circle. This group, which Davies joined, was formed of like-minded middle-class women who discussed contemporary matters and later campaigned on improving women’s lives.

In 1862 Davies briefly took over the work of editing The English Woman’s Journal, whose offices were based at 19 Langham Place. She also began her political work when Elizabeth Garrett found she could not enter a medical school without an initial university matriculation. Garrett’s difficult path to becoming a doctor can be followed in a series of important letters (now digitised) from her to Emily held in The Women’s Library. There are no surviving letters from Davies to Garrett. Working with the Langham Place Circle, Davies drafted a memorial to be signed by London University members, and other prominent people, to ensure that the university was open to everybody including women. So began Davies’ committee and lobbying work. In April 1862, Garrett applied to the University of London for permission to matriculate. It was rejected by one vote.

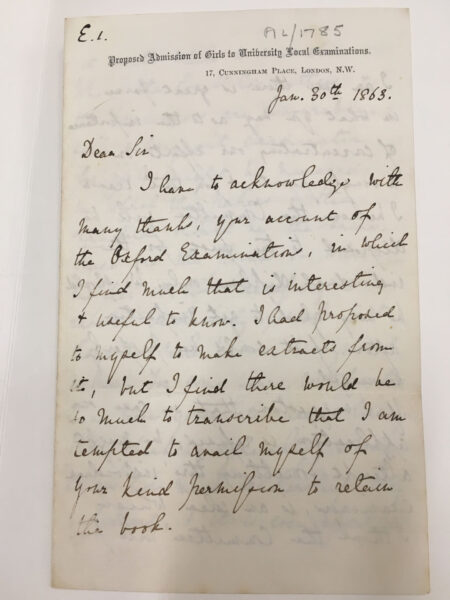

By the end of the year, Davies had begun her campaign to open University Local Examinations to girls. A committee was set up including Barbara Bodichon, Eliza Bostock, Isa Craig, Lady Louisa Goldsmid, Russell Gurney, James Heywood with Davies as secretary. She wrote to academics in London and beyond gathering support. Davies’ letters held in The Women’s Library are to Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, who had helped to establish the Oxford Local Examinations system in 1858.

The letters show Davies constructing arguments as to why girls should sit these examinations and offering solutions to perceived problems. For example, to the suggestion that boys and girls should not be examined in the same room, Davies suggested Lady Visitors chaperone girls as they had at Bedford College.

Bedford College in Bloomsbury was founded in 1849 by Elizabeth Jesser Reid at 47 Bedford Square. It admitted girls from the age of 12 and Lady Visitors chaperoned the girls to all lectures. Davies, herself, became a Lady Visitor in 1863. Later Davies became a member of a special committee which considered the College finances which led to the decision to raise fees.

In December 1863, the first examination of girls for Cambridge Local Exams took place as an experiment which revealed that girls’ education needed reform. Davies worked hard to make sure that girls’ schools were included in the Schools Inquiry Commission. In 1865 the Cambridge Senate voted to open Local Examinations to girls permanently.

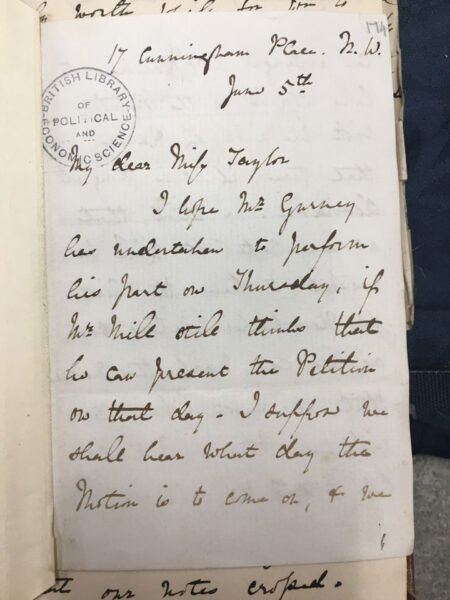

Davies was a member of the Kensington Society, a debating society, which held its first meeting in 1865. Many of the Langham Place Circle were also members. When Gladstone introduced the Reform Bill in the following year, the Kensington Society and the Langham Place Circle decided to circulate a suffrage petition. LSE Library holds letters which follow this campaign from its beginning (ref: Mill-Taylor).

Letter to Miss Taylor

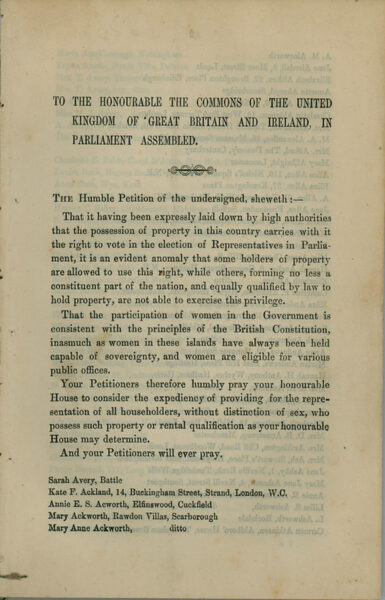

On 9 May 1866, Bodichon wrote to Helen Taylor (John Stuart Mill’s step-daughter) about starting a petition on women’s suffrage. Davies edited Taylor’s draft. The petition asked for the representation of ‘all householders without distinction of sex’. During May and June, the group collected 1,500 women’s names. On 7 June 1866, Davies and Garrett handed the petition to John Stuart Mill in Westminster Hall. This is depicted in Bertha Newcombe‘s 1910 painting. Stuart Mill presented the petition to Parliament. Although it was rejected, the group was undeterred. This was the start of the long campaign for women’s suffrage.

The original petition has not survived. Before it was lost, it was printed as a pamphlet so that it could be sent to newspapers subsequently. There are only two known copies of this pamphlet – one held in Girton College and the other in The Women’s Library.

Davies’ campaigning work continued. She formed the London Association of Schoolmistresses and a committee to found a College for Women. This opened in 1869 at Hitchin in Hertfordshire with five students, moving to Cambridge, as Girton College in 1873. Davies was Mistress of Girton until she retired in 1875. She then renewed her work on women’s suffrage. Here is an image of Emily taking part in the first women’s suffrage procession in London organised by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies in 1908. Davies can be seen second on the right of the front row of women which includes Frances Balfour, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Ethel Snowden and Sophie Bryant. Davies died in 1921 having voted in the 1919 General Election.

Further reading:

Emily Davies: Collected Letters 1861-1875, edited by Ann B Murphy and Deidre Raftery (University of Virginia Press, 2004).

Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Reference Guide (UCL, 1999).

Elizabeth Crawford, The Enterprising Women: The Garretts and their Circle (Francis Boutle Publishing, 2002).

Margaret Tuke, A History of Bedford College for Women 1849-1937 (Oxford University Press, 1939).

Barbara Stephen, Emily Davies and Girton College (London, 1927).

Find out more about the resources relating to women’s suffrage at LSE Library.

“If it be admitted that the law of human duty is the same for both sexes, it appears to follow that the education required is likely to be, in its broader and more essential features, the same.” (from The Higher Education of Women 1866)

Gillian Murphy is the Curator for Equality, Rights and Citizenship at LSE Library. She promotes collections that relate to rights and equalities which is mainly working with The Women’s Library and the Hall-Carpenter Archives. She organises various engagement activities which draw on the collections. These range from curating public exhibitions, planning events and talks to holding workshops for people to experience the material we hold. We welcome researchers, students, teachers, community groups, activists and the media to use our collections.

MINI BIOGRAPHY

Education:

Very little formal education: refused a serious schooling at home or at school, unlike her brothers. Was expected to help with ‘women’s work’ in the house.

Some Key Achievements and Interests

1860-61 founded the Northumberland and Durham branch of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women (SPEW).

1860s Published letters in a Newcastle newspaper to promote women’s education and employment.

1862 “Medicine as a Profession for Women” paper read to the Congress of the Social Science Association (SSA) when it met for the first time in London. At the Congress Davies and France Power Cobbe presented papers arguing for women’s right to higher education and their admission to examinations and degrees. They were supported by the SSA’s council who resolved to appeal to the Senate of the University of London to consider opening examinations to women.

1862-1864 Writer for and Editor of The English Woman’s Journal.

1862 Secretary of the committee to promote the admission of women to university examinations. (Women were not admitted to London University degree examinations until 1878.) *

1862 Set up a committee to campaign for girls to be admitted to the University Local Examinations for schoolboys. Access for girls to the ‘Cambridge Locals’ was formalised in 1865 following a successful trial period.

1864 Helped found the Victoria Magazine.

Mid 1860s Active in the campaign for women’s suffrage.

1864 Successfully campaigned for the inclusion of girls’ schools in the remit of the Government appointed a Schools Inquiry Commission (The Taunton Commission) set up to examine middle-class secondary education and make recommendations on how to improve it.

1865 Presented evidence to the Taunton Commission on the state of female education, becoming the first women to give evidence in person to a royal commission as an expert witness. The publication of the Commission’s report led to the Endowed Schools Act and other reforms.

1865 Secretary of the Kensington Society, a debating group for women that petitioned for women’s suffrage.

1866 Started the London Schoolmistresses’ Association.

1866 With Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon drew up a petition to ask Parliament to grant the vote to women with the same property qualifications as male voters. Despite 1,500 signatories and the support of John Stuart Mill, this did not succeed.

Fearing that her involvement with more radical suffrage campaigners would detract from her campaigning for women’s education, she then took a back seat from the former until the 1890s.

1866 Set up a fund raising committee which raised funds enabling the founding of The College for Women in 1869, renamed Girton College in 1872, and with which she continued to be actively involved.

1870-1873 Sat on the London School Board as a member of the Greenwich Division, (along with Elizabeth Garrett for the St Marylebone Division), sitting on the Statistical Committee and the Bye-Laws Committee. Local school boards took responsibility for the building and running of schools in their area.

1891 Joined the Executive Committee of the London National Society for Women’s Suffrage (LNSWS) becoming actively involved again in campaigning for women’s suffrage.

Issues

Wanted to pursue medicine as a career but felt her lack of education disadvantaged her. Instead, she focussed on campaigning for girls’ education and women’s higher education.

Her elder sister and two brothers were seriously ill in late 1850s (they died in 1858) and this affected her profoundly

Tried unsuccessfully to get the University of London to admit women students. She believed resistance was because of conventions that could be overturned and not essential differences between the sexes.

Connection to Bloomsbury

1863-1864 Lady Visitor at Bedford College, Bedford Square. (Lady Visitors were tasked to attend some lectures as chaperones of the young ladies).

Networked in the area.

Female Network – extensive including:

Close friends: Anna Richardson, Annie and Jane Crow, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson.

Bessie Raynor Parkes, Emily Faithfull.

Elizabeth Blackwell (whose lectures she attended).

Other members of the Kensington Society: Dorothea Beale, Elizabeth Wolstenholme, Frances Buss, Frances Power Cobbe, Helen Taylor, Isa Craig, Sophia Jex-Blake.

Members of the London Schoolmistresses’ Association: Charlotte Manning, Fanny Metcalfe, Frances Buss, Jane Chessar.

Writing/publications include:

Articles in The English Woman’s Journal and The Victoria Magazine eg; Female Physicians, The English Woman’s Journal, May 1862; The Influence of University Degrees on the Education of Women; The Victoria Magazine, June 1863.

1862 Paper read at the Social Science Congress June 1862: Medicine as a profession for women.

1866 The Higher Education of Women

1896 Women in the Universities of England and Scotland

Further reading:

“Personal Papers of Sarah Emily Davies, 1856-1978”; Girton College Archive;

https://archivesearch.lib.cam.ac.uk/repositories/19/archival_objects/370725

“Davies, (Sarah) Emily”; The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Sara Delamont; 23 September 2004; https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-32741?rskey=lzzE1q&result=2

Kathleen E McCrone; The National Association for the Promotion of Social Science and the Advancement of Victorian Women, Atlantis Vol. 8 No 1 Fall 1982 44-66

*The Influence of University Degrees on the Education of Women printed in The Victoria Magazine, June 1863

Davies references attempts by women for admission to the examinations of the University of London which were met with the response that admission could not be legally granted. One attempt by a woman to be a candidate at the next Matriculation Examination, caused a resolution to be passed: ‘The Senate, as at present advised, sees no reason to doubt the validity of the opinion given by Mr Tomlinson, July 9th 1856, as to the admissibility of females to the Examinations of the University.’

However, this latest attempt had been Elizabeth Garrett and her father pursued the matter but still meeting with a refusal by the Senate.

Davies examines the cause of the Senate’s refusal: ‘They resolve themselves, for the most part, into an ‘instinct’, a prejudice, or an unproved assertion that women ought not to pursue the same studies as men; and that they would become exceedingly unwomanly if they did. A woman so educated would, we assured, make a very poor wife or mother. Much learning would make her mad, and would wholly unfit her for those quiet domestic offices for which Providence intended her. She would lose the gentleness, the grace, and the sweet vivacity which are now her chief adornment, and would become cold, calculating, masculine, fast, strongminded, and in a word, generally unpleasing. That the evils described under these somewhat vague terms are very real, and do actually exist at this moment, cannot be denied by anyone who is at all conversant with English society. That any scheme of education which might tend to foster them ought to be energetically resisted, will scarcely be disputed by any – least of all by the advocates of extended mental culture for women.’