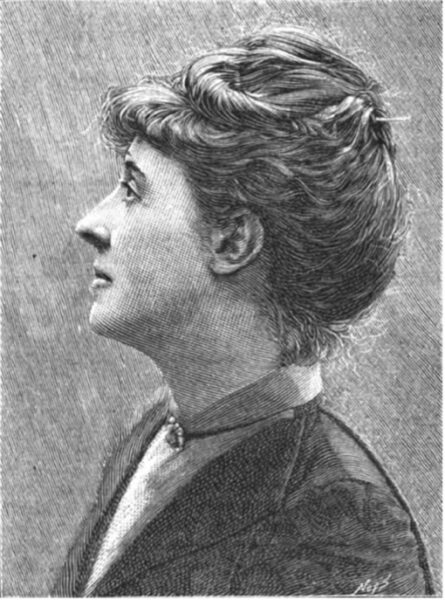

Mona Caird 1854 – 1932

(née Alice Mona Alison; also known as Alice Mona Henryson Caird)

Essayist, novelist, suffragette.

24 May 1854 – 4 February 1932

Mona Caird: The “Priestess of Revolt”

A tribute by Rachel Newman

H. S. Mendelssohn (1894)

Published in The Review of Reviews, 1894

Murray McNeel Caird Urquhart (1918)

Santa Barbara Museum of Art

Before the late 1880s Anglo-Scottish writer Mona Caird [1854-1932] was practically unheard of but, by the 1890s, she was recognised as a radical thinker about the woman’s sphere and the role of marriage in late Victorian culture. As an influential writer and activist in the fin-de-siècle period, she argued for greater social, legal, and political equality for women, as well as changes to women’s education and their status within the marriage institution. In August 1888, Mona Caird published two articles, entitled ‘Marriage,’ and shortly after that, ‘Ideal Marriage’ in The Westminster Review, claiming that marriage was a ‘vexatious failure’ for society and for women in particular. The ensuing debate in print, regarding the status of women and marriage, gave Caird’s ideas great visibility and garnered widespread public attention, resulting in what has been called ‘the greatest newspaper controversy of modern times’ (Heilmann 70).[1] Caird argued that, until women were permitted to control and own their own bodies, marriage was ‘the degradation of womanhood’ (Heilmann 70). The Daily Telegraph asked its readers to respond to the question inspired by Caird’s original article, ‘Is Marriage a Failure?’ and over 20,000 letters were sent in response, igniting a firestorm of controversy around central questions pertaining to women and their place within marriage, the home and society more broadly (Pykett 144). In 1892 as a result of this polemical debate, popular journalist W.T. Stead describes her as ‘the priestess of revolt’ who ‘sympathises with revolters everywhere.’ Another review in The Academy also remarks that ‘it is impossible to say whether she is a born novelist or merely a born controversialist.’ This gives an idea of the controversy and uproar that Caird stirred in the 1890s.

Very little is known about Mona Caird’s early life; what is known has been written about by Ann Heilmann in her 1995 article, ‘Mona Caird (1854-1932): Wild Woman, New Woman, and Early Feminist Critic of Marriage and Motherhood.’ She was born Alice Mona Alison on the Isle of Wight in 1854 and, upon her marriage in 1877 to Scottish gentleman James Alexander Henryson Caird, she became known as Alice Mona Henryson Caird, or Mona Caird. While her husband and son remained at Cassencary, the Scottish family estate, Mona Caird spent the majority of her marriage and most of her career and later life in London. There she became an author of fiction and nonfiction essays. Caird published a short story satirising the New Woman figure of the fin de siècle, ‘The Yellow Drawing Room’ (1892) and she also wrote several important novels in dialogue with the Woman Question and the New Woman movement of the 1890s: The Wing of Azrael (1889), The Romance of the Moors (1891), The Daughters of Danaus (1894), The Pathway of the Gods (1898) and, later, The Stones of Sacrifice (1915) and The Great Wave (1931). As an activist and suffragette, she was also a member of important political groups and movements, including the ‘Literary Ladies’ club (later called the Woman Writers club), the Theosophical Society, the Anti-Vivisection Club, the London Society for Women’s Suffrage, the National Society for Women’s Suffrage and the Women’s Franchise League.

Caird was based in London during a particularly transitional period in British culture. In the 1890s, alongside technological changes and the influence of new scientific methods of thought, there were vast legal and political changes. There were also anxieties expressed about waning British imperialism and societal ‘degeneration.’ In the literary marketplace there was an increase in journalistic fervour and the death of the three-volume novel, or the Triple-Decker. Many concerns of the fin de siècle hinged upon the social and legal status of women in Britain, which was increasingly debated in public. Much of this cultural anxiety circled around the ‘New Woman.’ This figure emerged in the 1890s periodical press to express many of the same fears regarding women gaining their own agency. The term was first coined by Sarah Grand in 1894 in ‘The New Aspect of the Woman Question.’ After this first usage, the concept of the New Woman was used both by both sides. If the male journalistic satirisation of the ‘mannish’ figure marketed her to oppose woman’s equality, the nineteenth-century suffragists appropriated her to champion their cause. In other words, the New Woman of the 1890s became the seat of many different socio-political anxieties related to both the tumult of the present moment and the uncertainty of the future.[2]

Caird’s literary contributions have been frequently overlooked in the midst of the controversy surrounding the New Woman figure and she has also been lost at times in this midst of the explosion of strange and fascinating fiction of the fin de siècle. She is frequently seen as part of the New Woman movement, although she did not always agree with other 1890s feminists. As a woman writing for other women, Mona Caird’s fictional and nonfictional investment in women’s issues was part of an attempt to provoke actual social and political change. In her fiction, Caird deconstructs previous models of the novel by re-imagining the nineteenth-century marriage plot novel as well as the Bildungsroman, or the novel of education. In The Wing of Azrael and The Daughters of Danaus, both of her female protagonists hesitantly enter marriages which quickly prove to be deeply unhappy. In The Wing of Azrael, the heroine plots to leave her abusive husband before eventually murdering him when he threatens her with rape and imprisonment. In The Daughters of Danaus, the heroine leaves her husband and children in order to pursue an artistic career. Both of these characters gradually realise that they are entrapped and stifled by their husbands and by the marriage institution itself. They attempt—sometimes successfully—to escape the stranglehold of Victorian marriage and motherhood even if it costs them their social standing and family which, as middle-class English women, ostracises them from ‘respectable’ society.

Caird’s nonfiction work had similar aims to challenge patriarchy. She combined her essays on marriage in 1897 in The Morality of Marriage: And Other Essays on the Status and Destiny of Women. In this work, she synthesises many of the ideas she initiated in her earlier articles and in her fiction, particularly focusing on the poor standards of education for women, the constrictions of women through domesticity, marriage and the family and the ways that these are pre-ordained for young women without their full comprehension of what such institutions entail. In The Morality of Marriage, Mona Caird points out that it is impossible that ‘the demand of women for freedom should become a feature of modern life, without the marriage-relation, as at present understood, being called in question.’ The female ‘claim[s] for freedom’ must include ‘a claim for a modified marriage’ (Caird 67). In this study, her main intention is not just to interrogate the ‘nature’ argument—holding that the traditional societal means of managing marriage and the family are ‘natural’—she also looks to equalise laws surrounding divorce for both men and women and to initiate a ‘greater measure of justice as regards parental rights following separation and divorce. Caird also opposes the stereotype of woman as the ‘weaker sex’ which renders women as infantile and incapable. In doing so, Caird advocates for easier pathways to education and employment for middle and upper-class women. This is to empower and enfranchise them and offer alternative options other than marriage (9).

It is difficult to say how much time Mona Caird spent in Bloomsbury because there is no existing archive for Caird containing her letters, papers, writings, or other possessions. While not a formal member of the group (possibly because her views were seen as too radical and uncompromising), she did attend some meetings of Karl Pearson’s Men and Women’s Club of London in the 1890s, which was founded as ‘a forum for the discussion of sexual matters.’ She would have intermingled with other activists and thinkers through that setting (Heilmann 72). We also know that Caird networked in and around the British Museum Reading Room and that she interacted with other prominent literary figures who frequented the area. These included Thomas Hardy, Olive Schreiner, and Eleanor Marx.

Mona Caird was a radical thinker, but more than that, she challenged the very structure of the nineteenth-century marriage plot novel as a mirror of an ideal, patriarchal society. She played a critical role in the cultural conversation surrounding the role of women in society and within marriage by demanding a complete revision of ‘the entire script on which society was based,’ through both her fiction and nonfiction, as well as her political activism (Heilmann 86). In a revealing discussion with a reporter for The Pall Mall Gazette in August 1888, “Free Marriage v. the Marriage Bond: An Interview with Mrs. Mona Caird,” Caird challenged the idea that “women are educated to regard emotion as the chief end in life.” In doing so, not only does she invite a rethinking of women’s education but she also calls into question what the “chief end in life” ought to be for women? If not “emotion”— which we might substitute for marriage, motherhood, and a domestic family life—then what? Without fully answering this question, Caird’s position as the so-called “priestess of revolt” enables her to suggest new possibilities for women to channel “emotion” in fresh ways.

—Rachel Newman

Rachel Newman is a Ph.D. Candidate in English Literature at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, CA. Her dissertation focuses on female anxiety and narrative form in fin-de-siècle female-focused fiction, specifically studying what she calls ‘anxious plotting’ in the novels of key late nineteenth-century authors, including Mona Caird, Sarah Grand, and George Gissing.

Works Cited—

Caird, Mona. The Daughters of Danaus. 1894. The Feminist Press at CUNY, 1993.

Caird, Mona. The Great Wave. 1st ed. Wishart & Co., 1931.

Caird, Mona. ‘Marriage.’ Westminster Review. 130. 1888. 186-201.

Caird, Mona. The Morality of Marriage: And Other Essays on the Status and Destiny of Women. George Redway, 1897. Reprinted, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Caird, Mona. The Pathway of the Gods. 1st ed. Skeffington & Sons, 1898.

Caird, Mona. The Romance of the Moors. 1891. Leopold Classic Library, 2016.

Caird, Mona. The Stones of Sacrifice. 1st ed. Simpkin, 1915.

Caird, Mona. The Wing of Azrael. 1889. Valancourt Books, 2010.

Caird, Mona. ‘The Yellow Drawing-Room.’ 1891. Dreams, Visions and Realities: An Anthology of Short Stories by Turn-Of-The-Century Women Writers. Ed. Stephanie Forward. University of Birmingham Press, 2003.

Heilmann, Ann. ‘Mona Caird (1854-1932): Wild Woman, New Woman, and Early Feminist Critic of Marriage and Motherhood.’ Women’s History Review, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1995.

Heilmann, Ann. New Woman Fiction: Women Writing First-Wave Feminism. Macmillan Press, 2000.

Heilmann, Ann. New Woman Strategies: Sarah Grand, Olive Schreiner, Mona Caird. Palgrave, 2004.

Ledger, Sally. The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siècle. Manchester University Press, 1997.

Ledger, Sally. McCracken, Scott. Cultural Politics at the Fin de Siècle. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Ledger, Sally. Luckhurst, Roger. Eds. The Fin de Siècle: A Reader in Cultural History c. 1880-1900. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Pykett, Lyn. The ‘Improper’ Feminine: The Woman’s Sensation Novel and the New Woman Writing. Routledge, 1992.

Stead, William Thomas. ‘Mrs. Mona Caird in a New Character.’ Review of Reviews, 1893.

Youngkin, Molly. Feminist Realism at the Fin de Siècle: The Influence of the Late-Victorian Woman’s Press on the Development of the Novel. Ohio State University Press, 2007.

[1] See Ann Heilmann’s article ‘Mona Caird (1854-1932): Wild Woman, New Woman, and Early Feminist Critic of Marriage and Motherhood’ in Women’s History Review (1995). Lyn Pykett also discusses the infamous publication of Caird’s articles in The Improper Feminine (1992).

[2] For more critical studies of the New Woman, see Gail Cunningham’s The New Woman in the Victorian Novel (1978), Sally Ledger’s The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siècle (1997), Sally Ledger and Roger Luckhurst’s edited volume, The Fin de Siècle: A Reader in Cultural History c. 1880-1900, (2000), Ledger’s Ann Heilmann’s New Woman Fiction: Women Writing First-Wave Feminism (2000), Molly Youngkin’s Feminist Realism at the Fin de Siècle: The Influence of the Late-Victorian Woman’s Press on the Development of the Novel (2007)

MINI BIOGRAPHY

Education

Conventional middle-class upbringing. Later self-educated reading very widely.

Some Key Achievements and Interests

1878 Became a member of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage.

1880s-90s Wrote on issues relating to marriage (particularly undesired marital sex), gender relations, and the value of careers for women. She argued that gender relations were constructed and that marriage should not involve duty or sacrifice but should be freely entered into by men and women and able to be dissolved. (see essays in Westminster Review and the Fortnightly Review)

Mid 1880s Engaged in discussion of relations between the sexes at meetings of the Men and Women’s Club (founded by Karl Pearson to discuss the relationship between the sexes).

1891 Joined the Women’s Franchise League and the London Society for Women’s Suffrage and The Women’s Emancipation Union, in 1892 reading her paper “Why Women Want the Franchise” at the Emancipation Union conference.

Appointed member of the first Council of the Women’s Emancipation Union.

Member of the Society of Authors and the Pioneer Club.

1904-1909 Member of the Theosophical Society.

1909-1913 Member of the London Society for Women’s Suffrage.

Campaigner against vivisection becoming, for a short period, President of the Independent Anti-Vivisection League. Two of her novels and her play The Logicians: An episode in Dialogue examined issues relating to animal protection. She compared the treatment of animals and women.*

Campaigner against eugenics concerned to protect the rights of the weak and powerless and against different ideas put forward by eugenic supporters. She argued that the environment greatly influenced human behaviour and took issue with the belief that it was mostly the result of inherited genes.

Experimented with the form of the novel in her examination of social issues.

Issues

Was seen as a very controversial figure writing and campaigning for women’s rights eg easier divorce for women, easier access to child custody and economic independence and also in relation to her anti-vivisection and anti-eugenics stance.

Confronted many with traditional expectations of a woman especially that of a married woman, writing controversially about these expectations:

In her 1888 essay ‘Marriage’ she writes of a woman being ‘punished for all sins and errors with a ferocity and a persistence specially reserved for a sex which is called weak … Truly the fate of woman, in its injustice, its debasement and humiliating pain, is a tragedy such as Shakespeare never wrote nor Aeschylus dreamt of.’

This essay was responded to in a series that ran in in The Daily Telegraph titled ‘Is Marriage a Failure?’ which prompted 27,000 responses. Caird then wrote 1888 essay ‘Ideal Marriage’ to clarify her arguments.

In Phases of Human Development, Caird writes about the consequences of marriage: ‘To place the sexes in the relationship of possessor and possessed, patron and dependent, is almost equivalent to saying in so many words, to the male half of humanity: “Here is your legitimate prey, pursue it.”’

Her campaigning against vivisection alienated her from her husband and son who both hunted and fished.

Connection to Bloomsbury

Worked and networked in the British Museum Reading Room in Bloomsbury (ticket issued 1879).

Female Networks include:

Childhood friend Elizabeth Sharp, an anthologist.

Members of the Men and Women’s Club including: Olive Schreiner, Annie Besant, Eleanor Marx, Emma Brooke.

Annie Besant, Augusta Webster, Dinah Mulock Craik, Elizabeth Sharp, Katharine Tynan, Mathilde Blind, Rosamund Marriott Watson, Sarah Grand.

Corresponded with Jane Francesca, Lady Wilde (1821-1896), known under her pen name Speranza.

Writing/Publications include:

Numerous articles and essays (many published in Westminster Review and Fortnightly Review)

Articles 1884-1894 Collected and published as a book 1897 The Morality of Marriage and Other Essays on the Status and Destiny of Women.

1883 Whom Nature Leadeth published under pseudonym G Noel Hatton

1887 One That Wins published under pseudonym G Noel Hatton

1889 The Wing of Azrael

1891 A Romance of the Moors

1892 The Yellow Drawing Room

1894 The Daughters of Danaus

1895 The Sanctuary of Mercy

1898 The Pathway of the Gods

1896 Beyond the Pale

1902 play: The Logicians:An episode in dialogue

1908 essay: Militant Tactics and Woman’s Suffrage

1915 The Stones of Sacrifice

*Quote from an Essay that appeared in the Westminster Review – transcribed with footnotes by George P Landow and accessed from The Victorian Web http://www.victorianweb.org “Marriage” by Mona Caird (victorianweb.org)

Humane people ask his master: “Why do you keep that dog always chained up?”

“Oh he is accustomed to it; he is suited for the chain; when we let him loose he runs wild.” So the dog is punished by chaining for the misfortune of having been chained, till death releases him. In the same way we have subjected women for centuries to a restricted life, which called forth one or two forms of domestic activity; we have rigorously excluded (even punished) every other development of power; and we have then insisted that the consequent adaptations of structure, and the violent instincts created by this distorting process, are, by a sort of compound interest, to go on adding to the distortions themselves, and at the same time to go on forming a more and more solid ground for upholding the established system of restriction, and the ideas that accompany it. We chain, because we have chained. The dog must not be released, because his nature has adapted itself to the misfortune of captivity.”

Further reading:

The Morality of Marriage; The British Library;

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-morality-of-marriage

“Mona Caird – The Priestess of the Late Victorian New Woman’s Revolt”; The Victorian Web; https://victorianweb.org/authors/caird/bio.html

“Mona Caird Biography”; Victorian Era; https://victorian-era.org/famous-female-writers-of-victorian-era/mona-caird-biography.html#The_famous_works_and_publications_of_Mona_Caird

The Palgrave Encyclopaedia of Victorian Women’s Writing; Springer Link; https://link.springer.com/referencework/10.1007/978-3-030-02721-6