Edith 1869 – 1938 & Florence 1870 -1932 Stoney

Edith Anne Stoney 6 January 1869 – 25 June 1938

&

Florence Ada Stoney 4 February 1870 – 7 October 1932

Medical physicists, x-ray pioneers

The amazing Stoney sisters, Edith (1869–1938) and Florence (1870–1932)

A tribute by Henrietta Heald

Their pioneering work in radiology and knowledge of electricity saved many lives

The Dublin-born sisters Edith Anne Stoney and Florence Ada Stoney both had strong links with the London School of Medicine for Women in Hunter Street, Bloomsbury, now part of UCL Medical School.

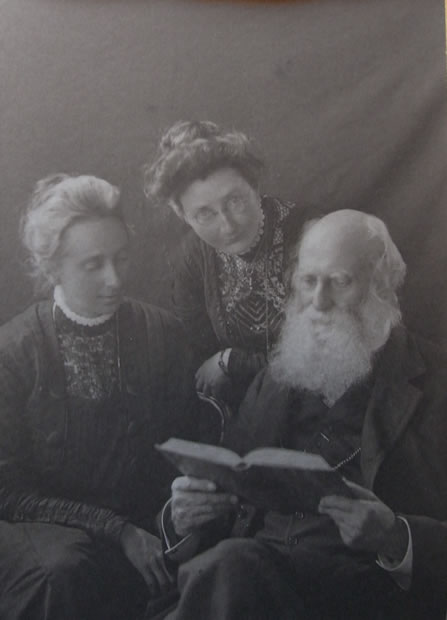

The Stoney sisters’ academic prowess was evident from an early age, but Trinity College Dublin – where their father, Dr George Johnstone Stoney FRS, taught mathematics and physics – did not admit women, so, after initial schooling in Ireland, the sisters were educated in England.

Johnstone Stoney, who championed education for women, is best known for coining the term ‘electron’ in 1891 as the fundamental unit quantity of electricity. Among his students at Trinity was Charles Parsons, the future inventor of the compound steam turbine, which would revolutionise the propulsion of ships and make possible the generation of electricity on a vast scale.

Edith Stoney won a scholarship to study mathematics at Newnham College, Cambridge, and in 1893 achieved among the top marks for her year, but at that time (and for another 55 years) Cambridge did not award degrees to women, so she did not officially graduate; she was later awarded BA and MA by Trinity.

Edith’s ‘great and original ability for applied mathematics’ was recognised by Charles Parsons, who had set up a firm in Newcastle upon Tyne to manufacture turbines and commissioned her to do some calculations relating to his experimental little ship, Turbinia. In a letter of 1903 to Johnstone, his former tutor, Parsons wrote admiringly, ‘Your daughter … made calculations in regard to the gyrostatic forces brought on to the bearings of marine steam turbines through the pitching of the vessel, and showed that such forces were not sufficiently large to cause trouble in practice.’

In 1899, at the age of 30, Edith had been appointed physics lecturer at the London (Royal Free Hospital) School of Medicine for Women in Hunter Street, established in 1874 by Sophia Jex-Blake, where her first tasks were to set up a physics laboratory and design the physics course. She continued in this post until the start of the First World War. According to one obituarist, Edith was ‘perhaps too good a mathematician’ to understand the struggles of the average medical student. ‘Her lectures on physics mostly developed into informal talks, during which Miss Stoney, usually in a blue pinafore, scratched on a blackboard with coloured chalks, turning anxiously at intervals to ask ‘Have you taken my point?”’

During the 1890s, Florence Stoney, Edith’s younger sister, had acquired a number of qualifications from the London School of Medicine for Women, including MD in 1898. At a time when the apparatus and facilities were still at a primitive stage, she started administering X-rays at both the Royal Free and Garrett Anderson Hospitals. She also worked as a demonstrator in anatomy at the London School of Medicine, while building up a general practice in London.

When war broke out in August 1914, Florence assembled a medical team staffed entirely by women and, with Edith’s help, they constructed a portable X-ray machine. The group of 30 travelled in September 1914 to Antwerp, where they converted an old music hall into a fully equipped surgical hospital with X-ray installation. Within a few days, more than 130 wounded British and Belgian soldiers were receiving treatment.

Antwerp was bombarded the following month, forcing the evacuation of the hospital, and the women had to flee on foot and by bus to the Netherlands, crossing a bridge over the River Scheldt 20 minutes before the Belgians blew it up. The American consul-general at Antwerp wrote, ‘One of the first buildings to be shelled was the hospital run with such magnificent efficiency by the British women doctors.’

By November 1914, at the request of the French Red Cross, Florence Stoney’s medical team was installed in Chateau Tourlaville, near Cherbourg, where they had to arrange makeshift sanitation, water and heating. Using the power of a river in the grounds, they generated their own hydroelectricity for lighting the 72-bed hospital and operating the X-ray machine. Over the next few months, a constant stream of badly wounded French soldiers arriving by ship from Dunkirk were treated by the women.

Returning to England in March 1915, Florence was one of the first female doctors to be accepted for full-time work by the War Office, when she was appointed head of the radiological department of the 1,000-bed Fulham Military Hospital. For a long period, she was the only woman member of the medical staff, which dealt with more than 15,000 cases in the course of the war, since other hospitals sent wounded men there for localisation of bullets by X-ray. On demobilisation in June 1919, Dr Stoney was awarded an OBE.

Edith Stoney, meanwhile, was doing equally important work with X-rays and electricity. In 1915 she joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals and served with them in a tent hospital at Troyes, southeast of Paris – a venture funded by the Cambridge women’s colleges, Girton and Newnham – where she established and ran an X-ray department. Edith’s great achievements lay in using stereoscopy to locate bullets and shrapnel in the human body; and in the use of X-rays to diagnose gas gangrene – an indicator of the need for immediate amputation to give any chance of survival.

Later in 1915, Edith accompanied the hospital unit to Serbia, where it had been directed by the French authorities. ‘Before leaving Paris she had the foresight to equip herself, at her own expense, with a portable engine [electric generator] – the committee having refused to sanction the expenditure,’ according to her Times obituary. ‘This action was soon justified, for, when the hospital was installed at Gevgheli, there was no electric supply. Thanks to her engine, not only was this the only British hospital able to work X-rays, but as a by-product of the work of the department Miss Stoney lighted the entire hospital with electricity.’

Edith continued this astonishing work throughout the war, particularly in Greece and France, and her service was recognised by several countries. Her awards included the Croix de Guerre from France, the Order of St Sava from Serbia, and the Victory and British War Medals from Britain. After the war, she resumed her former role as a leading light of the British Federation of University Women and campaigned energetically for the proper recognition and fair employment of women in the professions, including engineering. She became one of the earliest (and oldest) members of the Women’s Engineering Society, founded in 1919 by Katharine and Rachel Parsons, the wife and daughter of Charles Parsons. In 1936, two years before her death, Edith established the Johnstone and Florence Stoney Studentship, which is now administered by Newnham College and supports clinical medical students undertaking a period of study abroad.

Henrietta Heald is the author of Magnificent Women and Their Revolutionary Machines (Unbound, 2019), about the extraordinary individuals who set up the Women’s Engineering Society after the First World War. The society, which is still thriving today, was formed by a group of women who had worked in the munitions factories and other wartime industries, some in highly skilled jobs, and objected to being told to ‘go back to the home’ when the war ended. Led by Rachel and Katharine Parsons, and backed by prominent political figures such as Nancy Astor, Ellen Wilkinson and Margaret Rhondda, they campaigned from the start for women’s employment rights and equal pay with men.

The Genius of the Parsons Family: https://parsonstown.info

Magnificent Women in Engineering: http://www.magnificentwomen.co.uk

Electrifying Women: https://www.facebook.com/groups/2298747020160501/

The Women’s Engineering Society: https://www.wes.org.uk

MINI BIOGRAPHIES

Edith Anne Stoney 6 January 1869 – 25 June 1938

Education

Educated privately and then at the Royal College for Science of Ireland.

Some Key Achievements and Interests

Won a scholarship to Newnham College, Cambridge.

1893 Achieved 1st in Part 1 Maths Tripos at Newnham College but could not graduate with a degree as Cambridge did not award degrees to women until 1948.

Became life member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, one of few women members.

1899 Appointed Physics lecturer at the London School of Medicine for Women.

1902 Set up new x-ray service at the London School of Medicine for Women.

1904 Awarded an MA from Trinity College, Dublin when women were finally accepted.

First Honorary Treasurer and long-term member of the Federation of University Women campaigning for women to practice in law and take different senior roles traditionally filled by men.

1915-1919 Worked in field hospitals in France, Serbia then Salonica providing x-ray and electrotherapy services for the wounded.

Pioneered the use of stereoscopy to locate bullets and shrapnel in the body and s-rays to diagnose gas gangrene.

Awarded Croix de Guerre in France, the Order of Sava from Serbia and Victory and British war medals.

Spokesperson for the British Federation of University Women campaigning for equal opportunities for women in professional roles.

Established Johnstone and Florence Stoney Studentship for research.

Issues

Unable to qualify medically.

The sisters offered to provide a radiological service for the troops in Europe but their offer declined as they were women.

Connection to Bloomsbury

London School of Medicine for Women see: Sophia Jex Blake – Pascal Theatre Company (pascal-theatre.com)

Further reading

M Edith and Florence Stoney, X-ray pioneers .indd (bristolmedchi.co.uk)

Edith Stoney – Unsung hero of the Turbinia story… – July 2018 | Special Collections (ncl.ac.uk)

Florence Ada Stoney 4 February 1870 – 7 October 1932

Education

Educated privately and then at the Royal College for Science of Ireland.

Trained at the London School of Medicine for Women receiving MD in 1898.

Some Key Achievements and Interests

Worked as anatomy demonstrator at the London School of Medicine for Women and clinical assistant in ENT at the Royal Free Hospital.

1901 Appointed to post of medical electrician.

With Edith prepared to open new x-ray service.

Appointed head of the electrical department at the New Hospital for Women.

1906 Set up a Harley Street general practice.

1914 Set up hospital with x-ray equipment in Antwerp before being forced to flee to the Netherlands, later moving to France.

Appointed head of radiology at Fulham Military Hospital.

1919 Awarded OBE for her services at the Fulham Military Hospital.

Issues

The sisters offered to provide a radiological service for the troops in Europe but their offer declined as they were women.

Connection to Bloomsbury

London School of Medicine for Women see: Sophia Jex Blake – Pascal Theatre Company (pascal-theatre.com)

Further reading

M Edith and Florence Stoney, X-ray pioneers .indd (bristolmedchi.co.uk)