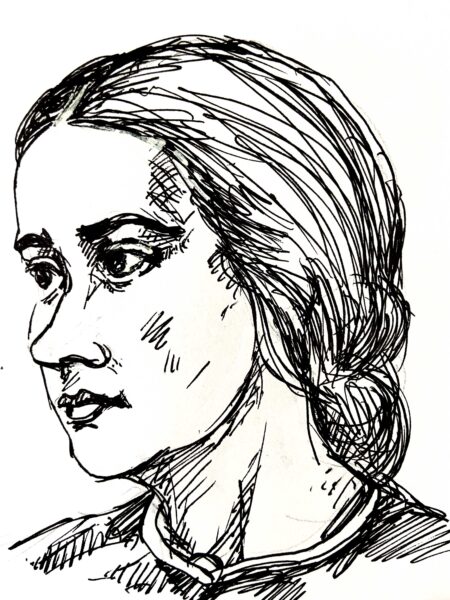

Sophia Jex Blake 1840 – 1912

Campaigner for medical education for women.

21 January 1840 – 7 January 1912

Photograph by Swaine of a portrait by Thomas Lawrence.

Wellcome Collection

Wellcome Images M0005996; Licensed under Creative Commons

Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1912): A Tribute by Patricia Fara

A fiery, impetuous woman, the pioneering doctor Sophia Jex-Blake bulldozed her way through gender barriers to create unprecedented opportunities for women. She secured her greatest achievement during the three years that she lived in Bloomsbury – the London School of Medicine for Women, which opened in 1874. For the next forty years, until the advent of the First World War, it remained the only place in England where women could train as doctors.

Throughout her life, Jex-Blake adopted strong-arm tactics to reach her goals of personal independence and equality for women. When she was eighteen, she confided to her diary that she had faked a fit of hysterics because she needed her authoritarian father’s permission to let her study at Queen’s College in London’s Harley Street. Her courses there included mathematics, natural philosophy and astronomy but in under three months she began tutoring other young women. At the same time, she was taking book-keeping lessons from the social reformer Octavia Hill, who described her as ‘a bright, spirited, brave, generous young lady, living alone, in true bachelor style.’

Jex-Blake’s next major step was to travel abroad. After a trip to Europe, she lived for several years in the United States of America, where she researched and wrote a book about progressive co-educational schools. It was during a spell in Boston as a nursing assistant that she decided on her life’s mission: enabling women to qualify as doctors, which would be liberating for them while also providing more sensitive and less embarrassing care for female patients.

After moving to Edinburgh, in 1869 Jex-Blake manoeuvred the University into enrolling women, eventually recruiting six other hopeful candidates to join her in an unconventional group that became known as the ‘Edinburgh Seven’. An independently wealthy woman, she was able to bankroll several of them for the exceptionally high fees charged by the lecturers for these unconventional and unwelcome newcomers. But even though they persevered through the course, male students protested, and the ‘Edinburgh Seven’ were assaulted on their way to their examinations – or as she put it, ‘a disturbance of a very unbecoming nature took place.’ The authorities then devised a series of blocking moves, culminating with a specially convened panel of judges that effectively banned women from receiving a degree. Undeterred by this Scottish setback, Jex-Blake moved to Bloomsbury, where she promptly embarked on another forceful campaign.

This time Jex-Blake proved invincible. Following some speedy fund-raising, on 12 October 1874 she opened her new London School of Medicine for Women in Henrietta Street, Brunswick Square. To ensure support, she stacked the Council with eminent doctors and scientists – such as Charles Darwin’s close colleague, Thomas Henry Huxley – and recruited an impressive array of lecturers to teach the first intake of fourteen students, which include herself as well as some followers from Edinburgh. Among other administrative triumphs, Jex-Blake linked her new School with the Royal Free Hospital, which had initially been set up to rescue sick people (notably female prostitutes) who could not afford medical care. Located in nearby Gray’s Inn Road, the Royal Free agreed to admit female students for the essential stage of clinical training with patients on the wards.

Acting as unofficial secretary to the School Council, Jex-Blake surmounted some formidable hurdles, even persuading two members of parliament to push through a bill that would allow examining bodies to accept women. The Irish College of Physicians was the first to take advantage of this new legislation, and after taking the preliminary precaution of a trial run in Switzerland, Jex-Blake travelled to Dublin, passed her examinations and became fully registered as a London doctor in May 1877.

Previously, there had been only two women on Britain’s Medical Register. The first was Elizabeth Blackwell, who qualified in the United States; she provided an inspiring role model for the second successful pioneer, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who took advantage of a temporary legal loophole at London’s Apothecaries’ Society to become the first British doctor. Garrett Anderson agreed to teach at Jex-Blake’s school, although she remained unconvinced that this was the best route for persuading the male-dominated medical profession to recognise female doctors.

Jex-Blake excelled at getting her own way through aggression rather than diplomacy. As just one example, her letter inviting Garrett Anderson to join the Council was laced with thinly disguised insults. ‘If I kept a record of all the people who bring me cock and bull stories about you, and assure me that you are “greatly injuring the cause,” I might fill as many pages with quotations as you have any patience to read,’ she began. The next paragraph opened in a similar vein: ‘Nor do I much care to know whether or not certain anonymous individuals have confided to you that they lay at my door what you call “the failure at Edinburgh,” – inasmuch as the only people really competent to judge of that point are my fellow-workers and fellow-students.’ She did at least manage to compose a conciliatory last sentence, and Garrett Anderson gracefully agreed to join the Council.

The committee meetings were stormy, and some of the relevant minutes have been carefully cut out of the records. Although Jex-Blake’s colleagues tactfully praised her energy and dedication, she seems to have been oblivious to any possibility of irony underlying apparent praise. ‘[W]e have just been saying that no one but you could have done all that work on Wednesday,’ soothed another female doctor ingratiatingly; ‘But indeed there is almost nothing that you don’t do better than everyone else.’

Gratified by her success, Jex-Blake assumed that she would be formally appointed honorary secretary of the London School of Medicine for Women, but even her allies felt worn down by her perpetually militant attitude. After another former student was chosen as a more diplomatic negotiator, in 1877 Jex-Blake retreated in a huff to Edinburgh, where she set up her own medical practice. Her life continued to be difficult. For two years, she suffered from depression and retreated into a solitary existence but then emerged to subsidise and found the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women. In an eerie reiteration of the past, after eleven years it was forced to close, torn apart by disputes between the students and the ever-domineering Jex-Blake.

Battling against the restrictions that stifled women in Victorian Britain, Jex-Blake launched the long struggle for gender equality in the medical world. Her reputation is blemished by reports that her aggressive behaviour antagonised colleagues as well as critics, although much of the hard evidence about head-on confrontations has vanished because she insisted that her papers be destroyed after her death. If she had been a man, her conduct would have been viewed differently. Perhaps the problem was not so much her belligerence but more her failure to respect highly gendered codes of etiquette: she adopted masculine tactics to prise open doors that were guarded by men.

Rosemary Ashton, Victorian Bloomsbury (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2012)

Patricia Fara, A Lab of One’s Own: Science and Suffrage in World War I (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018)

see also: Women and Madness – Pascal Theatre Company (pascal-theatre.com)

MINI BIOGRAPHY

Education

Home-educated until age the age of eight. Afterwards she went to private schools.

1858 Queen’s College.

Some Key Achievements and Interests

1874 Involved in founding the London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW).

1878 First practising female doctor in Scotland.

1888 Established the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women.

Issues

Jex Blake admitted to staging a fit of hysterics to force her father to let her study at Queen’s College.

Her parents believed it was wrong for middle-class women to work. When she was offered employment as a tutor, they agreed on condition she didn’t accept a salary.

Sophia Jex Blake’s father when she was offered a teaching position and he discovered this was waged responded: ‘I have only this moment heard you contemplate being paid for the tutorship. It would be quite beneath you, darling, and I cannot consent it. Take the post as one of honour and usefulness, and I shall be glad…. But to be paid for the work would be to alter the thing completely, and would lower you sadly in the eyes of almost everybody.’ Sophia replied: ‘Why should I not take it? You, as a man, did your work and received your payment, and no-one thought it any degradation… Why should the difference of my sex alter the laws of right and honour?’ quoted from Todd 1918

When she applied to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1869, she was rejected as the University ‘could not make the necessary arrangements in the interest of one lady’. When, with a group of other women she re-applied in 1869, they were accepted. Edinburgh became the first British university to admit women. However, some male students objected so strongly to women’s inclusion that female students were refused graduation. Jex Blake finally gained her MD, first in Berne and then in Dublin in 1877.

Connection to Bloomsbury

Lived 1874 in Bernard Street when opened School of Medicine.

London School of Medicine for Women opened 1874 initially in a small house, The Pavilion, rebuilt in 1898, in Henrietta Street (now Hunter Street).

Female networks

Jex Blake lived for a time with Octavia Hill’s family. She worked closely with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson although they disagreed initially on the question of single sex or mixed training. Jex Blake argued that training should be provided specifically for women in women-only spaces. Garrett Anderson thought that women should fight for equal access to education, within existing male dominated institutions. When Anderson was elected as Dean of The London School of Medicine in 1877, Jex-Blake retired, moving to Edinburgh where she set up the Edinburgh School. She connected to Elizabeth Blackwell and like-minded women.

Selected writing/publications include:

1869 Medicine as a Profession for Women, an essay.

1872 Medical Women: A Thesis and a History.

1893 article Medical Women in Fiction in periodical The Nineteenth Century.

Further reading:

Ashton, Rosemary. Victorian Bloomsbury, London: Yale UP, 2012

Todd, Margaret, The Life of Sophia Jex-Blake, London: Routledge,1918