Anna Atkins 1799 – 1871

(née Children)

Botanist, Photographer.

16 March 1799 – 9 June 1871

A Tribute by Ann Garascia

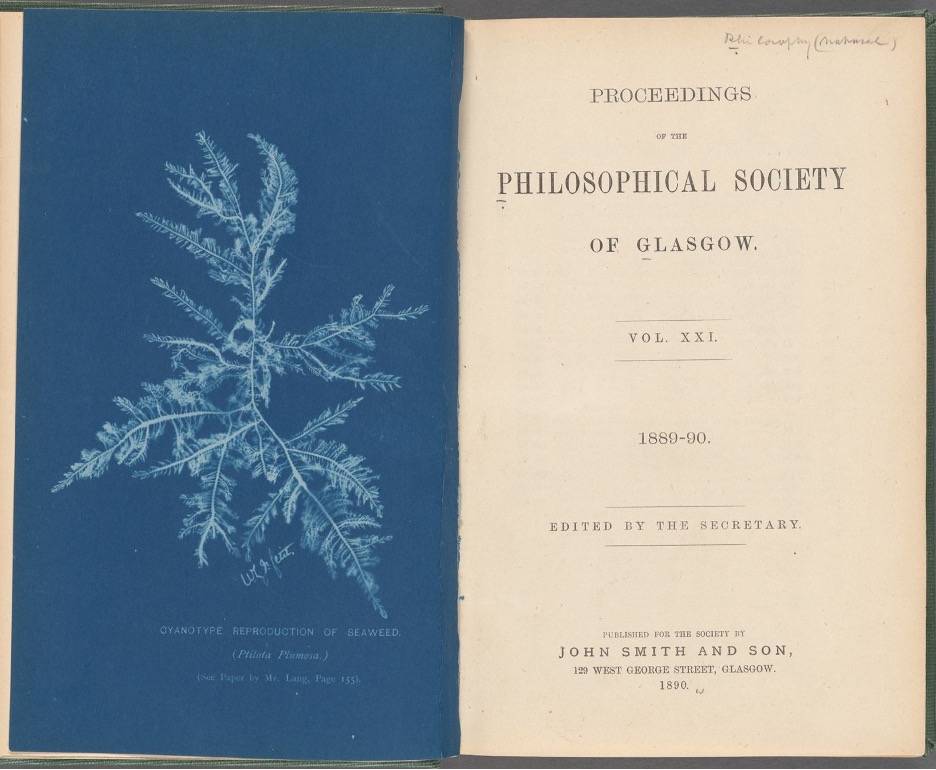

On November 6th 1889, historian William Lang Jr. excitedly presented to the Philosophical Society of Glasgow two unique volumes found in the British Museum. Sure to elicit interest from both a ‘photographic’ and ‘a natural history point of view’, the albums contained 379 photographic reproductions of British algae produced according to ‘one of the older photographic methods’ (1889 155). This ‘blue process’, as Lang coins it, refers to cyanotype making: a camera-less photographic technique that uses sunlight to imprint objects onto chemically treated paper. The resulting prints depict a process of metamorphosis through which the sticky olive greens and deep reds of living seaweed evaporate into gauzy ghosts of themselves suspended against an azure background. After detailing the cyanotype process, Lang finally identifies the artist, courtesy of James Britten, a botanist affiliated with the British Museum: the initials ‘A.A.’ belong to Anna Atkins, an artist and plant collector, whose father, John Children was stationed as Keeper of Zoological Department at the British Museum. Though the creator of the celebrated prints, Atkins herself feels as ghostly as her ectoplasmic algae prints look. Lang only speculatively remarks on her life and labours, admitting ‘how many copies of these cyanotype impressions were issued by Mrs. Atkins I have no means of knowing’. (157).

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/a3182ef0-0065-0136-bd23-5bb8787ea02d

This tribute to artist-botanist Anna Atkins maps out key moments in her intellectual-creative life that highlight her relationship to Bloomsbury’s Victorian centre of scientific knowledge, the British Museum. Traversing the familial and institutional, Atkins’s connections to the British Museum exemplify how nineteenth-century women scientist-artists carved out their own personal and professional networks.

Anna Atkins (née Children) was born in 1799 at Ferox Hall in Tonbridge, Kent. As her mother, Hester Anna Holwell, died shortly postpartum, Anna was primarily raised by her father John Children and grandfather George Children. An eminent scientist and Fellow of the Royal Society, John Children instilled in Anna a zeal for science, so for the Children scientific and artistic innovations proved foundational to the family unit. Without extensive personal records in the expected form of diaries or letters available, the most enduring evidence chronicling Atkins’ life are the artistic projects she both collaborated on and helmed herself.

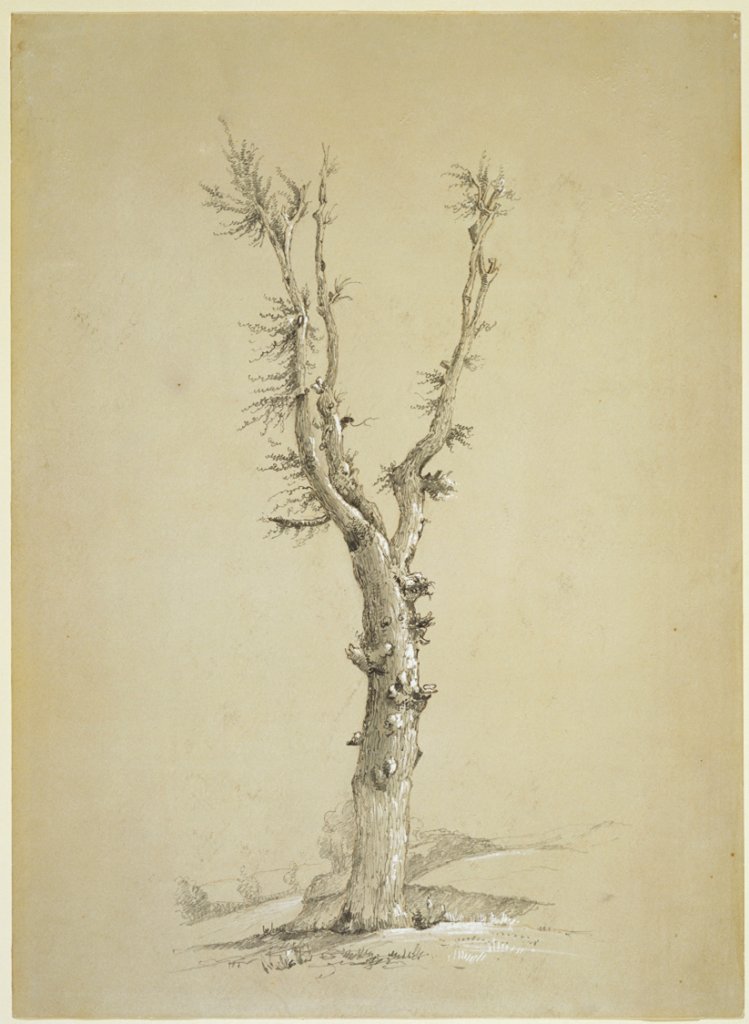

Inklings of Atkins’s botanical and artistic proclivities emerged in the form of a pencilled illustration titled The Waterloo Elm (1818). Once the command post for the Duke Wellington in the Battle of Waterloo, the dead tree was felled 1818; John Children purchased it, shipped it to England, and repurposed the wood into various souvenirs—with a scrap donated to the British Museum. Atkins’s sketch commemorates the tree’s final moments before the felling, the leafless tree standing staunchly and nobly. Her knack for delicate hatching, an artistic technique used to create tonal contrasts that wrap around the trunk, evokes a sense of verisimilitude that transports observers to the tree’s native environs.

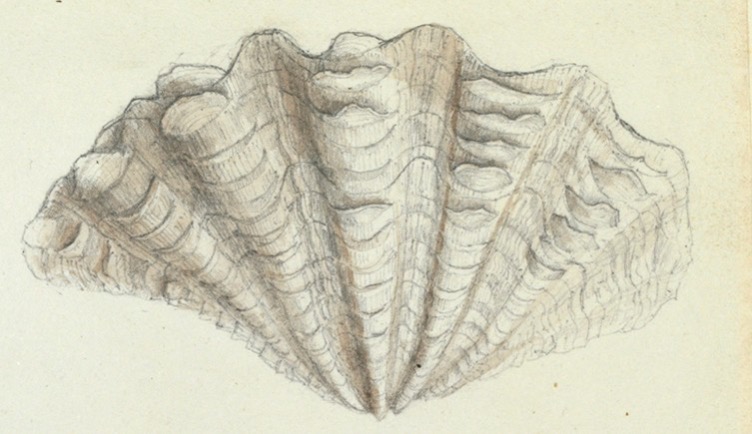

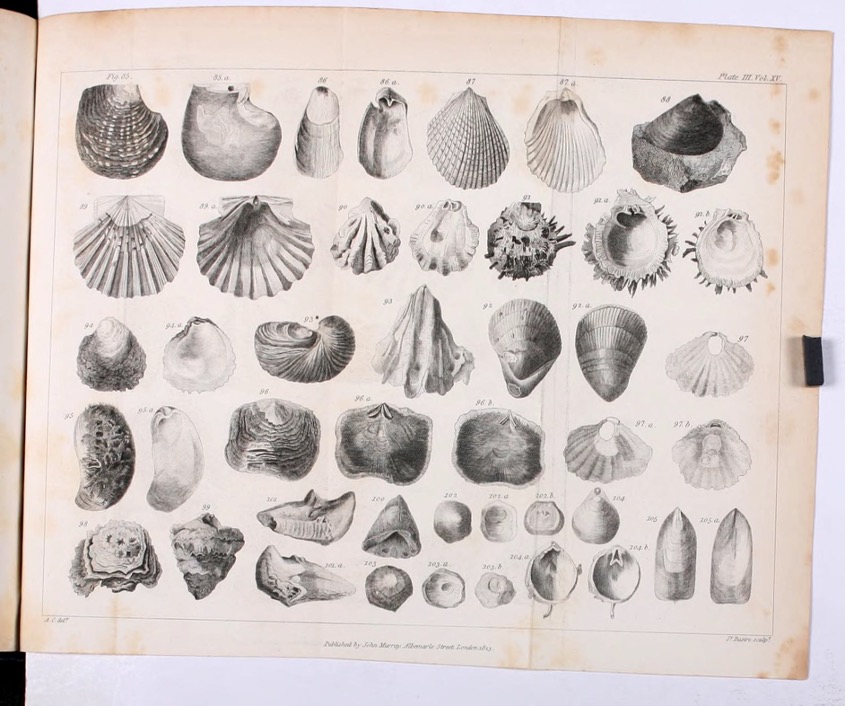

Her eye for fine-grained detail in illustration would have the chance to develop as her father’s position within the British Museum rose. After a stint as a librarian for the Department of Antiquities at the British Museum, in 1822 John Children secured a post as the Assistant Keeper of the Natural History Department; he worked closely with his assistant, John Edward Gray, who would become one of the British Museum’s most ardent taxonomists.[1] A year later, a messy collection of seashells at the Museum would offer Anna an opportunity to debut her well-honed artistic skills to the public. In her biography of her father, Memoir of J.G. Children (1853), Atkins explains that the ‘time and labour’ of organising the Museum’s shells inspired John Children to translate French conchologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s Genera of Shells, which featured accompanying illustrations by her (222-3). She originally composed her illustrations in graphite and watercolour before transforming them into engravings for intaglio printing suitable for publication. As expressed through her Tridacna gigas (giant clamshell), Atkins’ graphite originals capture the multi-textural qualities of the shells within their original aquatic environs, lending a quiet vivacity to the otherwise-two dimensional illustrations. In replicating the clamshell’s signature vertical folds, Atkins begins by carving out spaces of relatively deep shading before tapering to more faintly perceptible ripples, as though a beam of sunlight unevenly flashes over the shell. Her delicately undulating crosshatching confer a multi-dimensional texture to the shell, rendering the specimen at once smooth and roughhewn—a gentle reminder of the patterns of erosion and movements of water that subtly shape the shell over time.

Atkins’ role as an illustrator reflects the gendered dynamics of scientific work in the nineteenth century, and even earlier, as women found scientific illustration an art form that indulged their ‘innate curiosity and sensitivity’ toward the natural world (Tongiorgi Tomasi 2008, 161). By the nineteenth-century, women and visual production were so closely allied that an 1840 article in The Edinburgh Review euphemised the entire field of botanical illustration as the ‘the female pencil’. The father-daughter conchology collaboration afforded Atkins clear and public visibility as a serious scientific practitioner and creative artist, with her name appearing in full on the title page: ‘with plates from original drawings by Miss Anna Children’. Moreover, Anna’s shell illustrations enjoyed an afterlife beyond their original publication: an excerpted portion of Lamarck’s Genera of Shells in an 1823 issue of The Quarterly Journal of Science, Literature, and the Arts includes multiple fold-out composite engravings of Atkins’s illustrations.

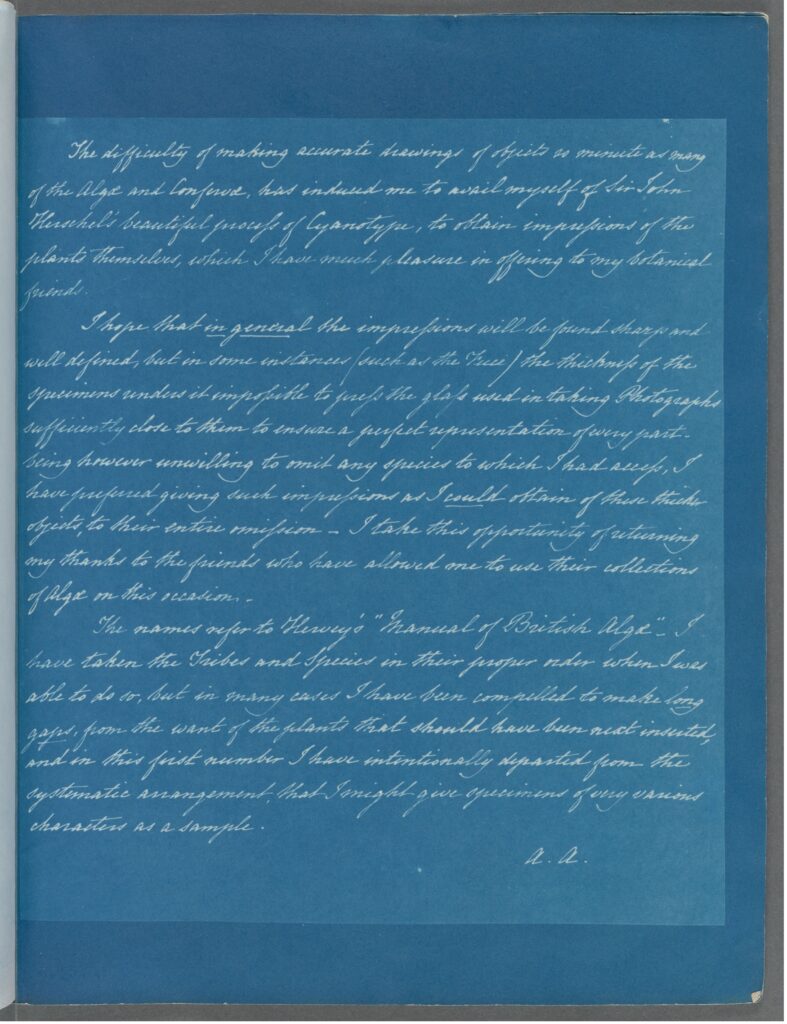

Atkins’ attention to the interplay of light and shadow in her illustration endeavours would come to inform her most extensive work, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. Her printmaking spanned nearly a decade (1843-1853) and would culminate in one of the first photographically printed books. Atkins’s introduction to Photographs of British Algae clarifies some of her inspirations, giving us increased insight into the British Museum’s subtler contributions to her project. She opens by specifically crediting ‘John Herschel’s beautiful process of Cyanotype’ as the ideal medium for accurately capturing ‘objects as minute as many of the Algae and Conferva’. Throughout the Victorian period, photography was marshalled to document the holdings found in the British Museum’s Assyrian and Natural History departments. The resulting ‘paper museums’ formed portable visual indices of the Museum’s collections (Davidson 2017). Excitement over early photographic methods permeated the intellectual and creative esprit of the Museum. Well-versed in chemistry and mineralogy, John Children’s research led to long lasting relationships with some the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries’ brightest photographic luminaries, like Humphry Davy, Thomas Wedgwood, William Henry Fox Talbot, and John Herschel. An enthusiastic devotee of early camera-less photographic processes, John Children often attempted to replicate photographic experiments in the home, especially John Herschel’s cyanotype process.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4b3b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

In 1825 Anna married merchant John Pelly Atkins and the couple settled into Halstead Place, the Atkins family home in Kent, which afforded her continued close contact with her father—and, by extension, the British Museum. Beginning as another father-daughter project, cyanotype making would soon become Anna’s signature medium. Her eagerness for the nascent photographic mode exemplified a broader cultural trend that linked cyanotype production and women’s handiwork. Photography enthusiast Robert Hunt recommended the cyanotype ‘to the study of ladies’ because it could faithfully replicate ‘botanical specimens’ and ‘patterns of needlework’ (7). Lauded for their simplicity and accuracy, cyanotypes, to Atkins, were the natural choice for documenting seaweed. To make her prints, Atkins would first sensitise writing paper with two chemical compounds, ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide. This step also attests to Atkins’ painterly skills since she employed brushing techniques common to watercolour painting to apply careful layers of the chemicals. After drying the paper, Atkins would arrange dried seaweed specimens on the treated paper, cover it in glass, and place it under the sun’s rays. After only a few minutes, the objects would be removed, and the paper would be dredged in water. The results featured strikingly white images of the imprinted object juxtaposed against a brilliantine blue background.

In addition to Herschel, Atkins briefly offers ‘thanks to the friends who have allowed me to use their collections of Algae on this occasion’. For nineteenth-century naturalists, collecting and classifying the diverse biota of the natural world was a most pressing task and the British Museum became a central hub for such activity. Gordon McOuat describes the Museum’s orderly and comprehensive reference systems as ‘exhaustive accounts’ and a ‘systema natura of all the known members of all the world’s living inhabitants’ (2001 6). With scientific research gravitating towards this definable centre, the heady atmosphere of the British Museum filtered outward with men, women, and children alike cultivating fervours for collecting the natural world. Atkins initially conceptualised her cyanotypes as collaborative project with another male scientist, as the prints were planned as visual accompaniments to William Harvey’s Manual of British Algae. Remnants of institutional collecting cultures still permeate Atkins’ images. Nodding to the Victorian preoccupation with classification, her introduction explains that the names included with each seaweed cyanotype ‘refer to Harvey’s Manual of British Algae.’ The prints themselves all observe a generalised formal unity reminiscent of museum herbaria: an isolated plant specimen with binomial Latinate name. Atkins’s project, however, evolved beyond these initial taxonomic aspirations to become a testament to the art of both the cyanotype process and seaweed itself.

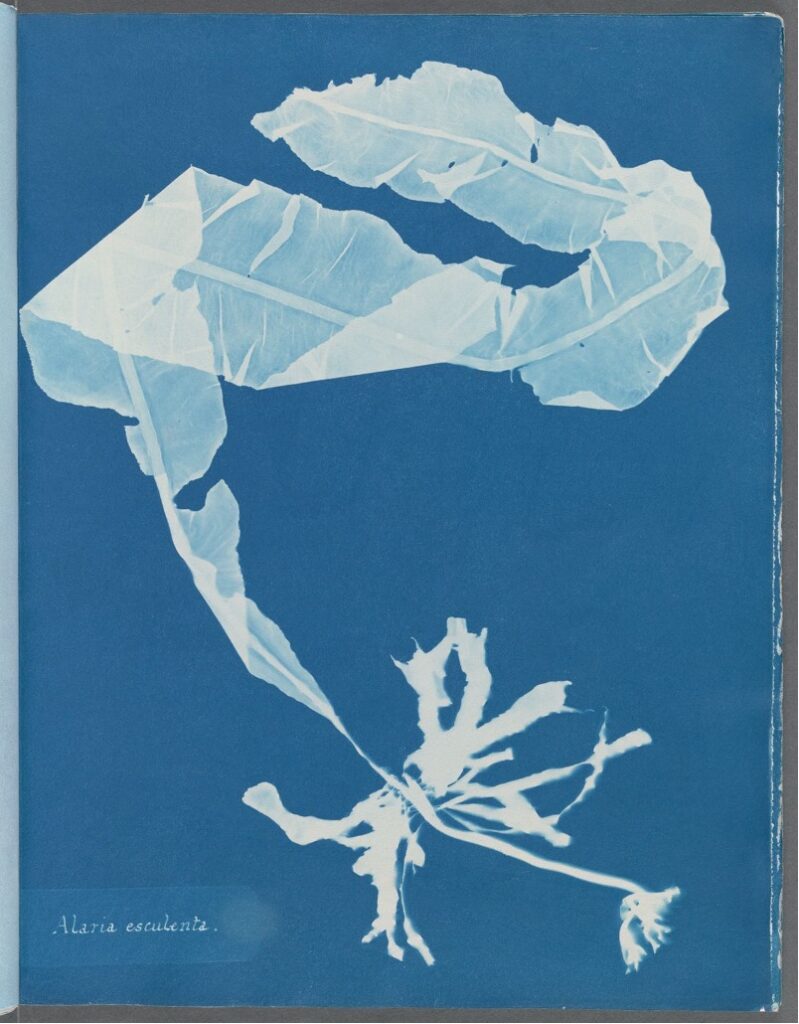

As a botanical collectible, seaweed was a much-revered plant during the mid-nineteenth century. Due to its shoreside ubiquity in England, seaweed especially attracted Victorian women collectors who, according to seaweed enthusiast Margaret Gatty, only needed a pair of waterproofed boots, ‘merino wool stock’ and an adventurous friend to procure the prized plants (1863 ix). Some of Atkins’ cyanotypes replicate the frisson that collecting could offer women. Her rendition of Alaria esculenta, an edible brown kelp, spotlights a thick, undulating frond while its opaque, massy holdfast (root system) anchors it in place. Torn in places from wind, surf, and littoral effluvia, the minorly imperfect plant and its billowing motions relocate observers to the British seaside the plants call home.

Atkins, Anna. Alaria esculenta. 1849-1850. Cyanotype. Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library. New York.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4ae9-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

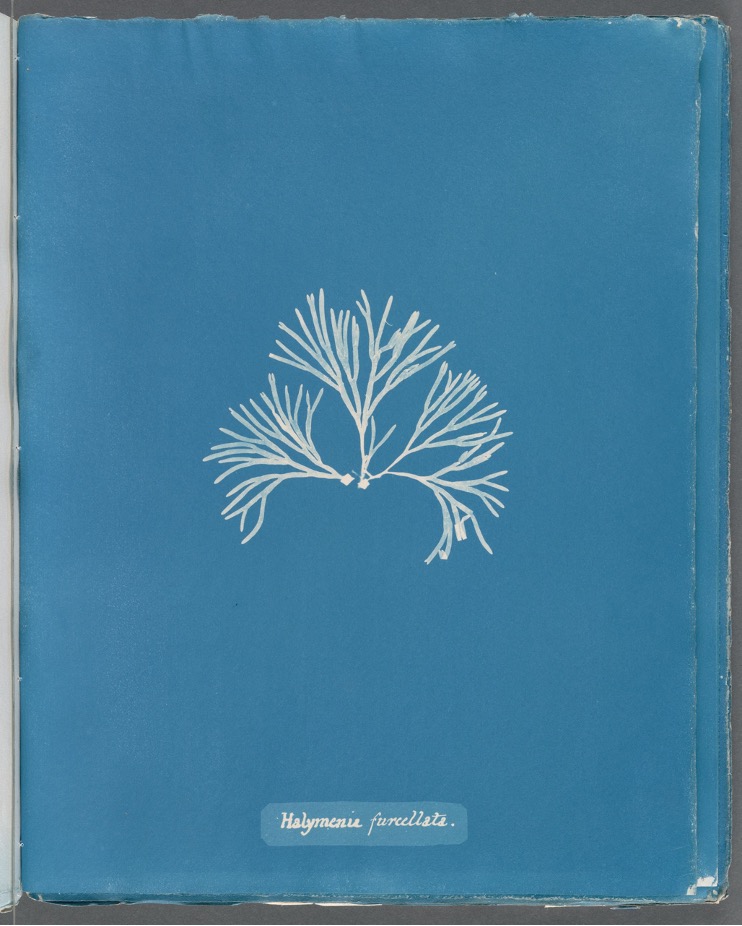

In addition to the act of collecting the plants themselves, geologist S.J. Mackie attributes the love of seaweed to its ‘elegance form and structure’ that renders the aquatic plant reminiscent of both ‘mathematical designs’ and ‘poetry’ (1872, 95). Atkins’s prints emblematise, and even enhance, these artistic merits accorded to seaweed. If the Alaria esculenta radiates the messy abundance of England’s shoreside environs, other prints, like the Halymenia furcellata, opt for a cleaner, sparer aesthetic. A trio of diminutive plants fans out gracefully, individual fronds carefully placed so as not to overlap. Reminiscent of a stylised sunburst peeking over the horizon, the graceful arc of fronds communicates a feeling of orderly calm that emphasises the gentle elegance inherent in seaweed. The artful arrangements Atkins composed signalled to her status as a woman artist, as popular science writer John Ellor Taylor avers that the ‘no fingers are so fitted for the delicate operation’ of arranging seaweed plants ‘than those of a lady’. (1880 49).

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4aaf-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Atkins viewed her project as a series of books, not just individual prints. For a decade, she would serially produce hand-sewn fascicles (a published instalment of a book) that included different algae cyanotypes and an accompanying page of contents listing the name of each plant. These bundles, tied carefully in blue paper, would be delivered to a group of Atkins’ choosing, including intimate friends and professional acquaintances, who would compile their installments into cohesive albums. Because Photographs was a privately printed endeavor, a complete list of the beneficiaries does not exist, although Larry Schaaf estimates that Atkins created nearly 6,000 prints. Notably, one album was bequeathed to the British Museum, which received thirteen different instalments from August 1843-December 1853. Perhaps reflecting the gendered nature of institutionally recognised scientific labour, Atkins did not present the prints herself, but rather employed a male proxy, John Edward Gray, who succeeded her father as the Keeper of Zoology. The album’s connection to the British Museum registers in the material condition of the album itself with the Museum’s red insignia stamped many of the pages.

Since Photographs of British Algae, Atkins’ presence within museum cultures has steadily been growing. A brief entry in the History of the Collections Contained in the Natural History Departments of the British Museum (1904) notes that Atkins presented her collection of ‘1,500 British Plants’ to the museum six years before her 1871 death. And as the opening anecdote of this tribute chronicles, in 1889, her collected works found audience beyond her circle of friends and the British Museum’s curators through William Lang’s laudatory presentation. Currently, Atkins’s works enjoy a widespread visibility and accessibility not necessarily afforded to her while living with partial and complete albums of Photographs of British Algae housed at museums world-wide, including the British Library, the British Natural History Museum, the New York Public Library, the Detroit Institute of the Arts, Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam), and the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum (Scotland), among others.

Dr Ann Garascia is a lecturer in the English Department at California State University San Bernardino. Her research interests include book history and archival studies, environmental humanities, and nineteenth-century British literature and culture. She is currently working on a book project that explores how Victorian women and plants collaborated to create innovative book objects. Her published writings appear in Victorian Literature and Culture, Journal of Ecohumanism, The European Journal for English Studies and other venues.

Works Cited

Atkins, Anna. Memoir of J.G. Children. Westminster, John Bowyer Nichols and Sons, 1853.

Davidson, Kathleen. Photography, Natural History, and the Nineteenth-Century Museum. Routledge, 2017.

Durham Athenaeum Soiree. Durham Country Advertiser, 24 March 1854, pg. 7.

Ellor,John Taylor. Half-hours at the Sea-side; Or, Recreations with Marine Objects. London, William Clowes and Sons, 1872

Gatty, Margaret Scott. British sea-weeds. Drawn from Professor Harvey’s ‘Phycologia Britannica’. With descriptions, an amateur’s synopsis, rules for laying out sea-weeds, an order for arranging them in the herbarium, and an appendix of new species. London,Bell and Daldy, 1863.

Lang, William. Cyanotype Reproductions of Seaweeds. Proceedings of the Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow Vol XXI, edited by John Mayer, 1889-90, Glasgow, John Smith and Son, pp 155-7.

Mackie, S. J. Sea-weeds as Objects of Design. Art Studies from Nature, as Applied to Design. London, Virtue & Co, 1872, pp. 91-132.

McOuat, Gordon. Cataloguing Power: delineating ‘competent naturalists’ and the meaning of species in the British Museum. British Journal of the History of Science, vol 34, 2001, pp. 1-28

Schaaf, Larry J. Sun Gardens: Victorian Photograms, Aperture, 1985.

Smith, James. Memoir and Correspondence of the late Sir James Edward Smith, MD. F.R.S. President of the Linnean Society. Edinburgh Review, edited by Pleasance Smith, Ballentine and Company, 1833, pp. 39-68.

Tomasi, Lucia Tongiorgi. La Femminil Pazienza: Women Painters and Natural History in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries. Studies in the History of Art, vol. 69, 2008, pp. 158–85.

[1] This appointment generated quite a bit of scandal amongst the scientific elite since Children’s knowledge of natural history was not nearly as comprehensive as that of his competitors. Children also disregarded more cutting-edge theories of geological development, denigrating them as “the trash vomited forth by Lamarck and his disciples (McOuat 11).