My Name is Dot

Dot

creative partner Lennie Varvarides

reader Samantha Leverette

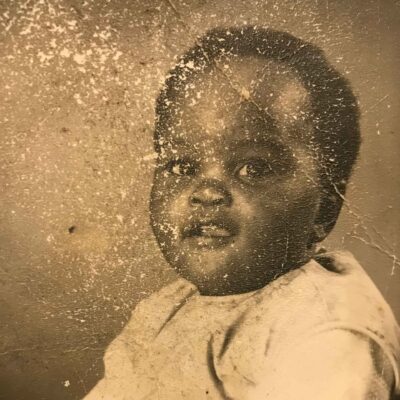

My name is Dot. I am my brother’s youngest sister. Just a dot in his memory. I am five and I miss him. Terribly. I am 85 and I miss him terribly. The blitz. Oursleepovers at the tube, my pink blanket in hand. I look up at my hero. Tall, him. Tall for his age him, or tall to five- year old me. When the siren starts we run. How he holds my hand as we run for our lives. I look up to him…my hero. I look up to him.

Underground, he makes sure I am covered tightly, that my head never touches the ground. For most, a good night’s sleep, underneath the bombing, it is cold and hard with only a promise that you might wake up. Now I know that we children were feral then. Then we were braver than kids now. Allowed our independence. Our parents cared that we survived, that was the struggle. In 1940, nobody was sentimental about kids. I am five. I have a pink blanket. It comforts me.

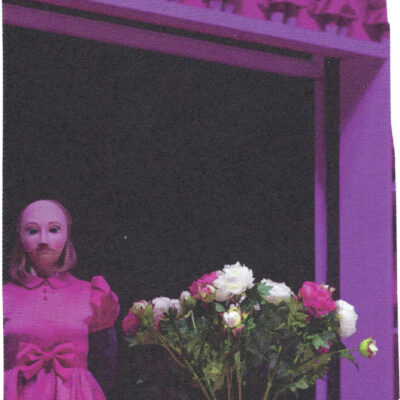

Mother held onto it, to keep things as normal as possible. Like the Queen’s annual parade. Our Mother uses her wages earned from her cleaning job to get us all new clothes. Mother wants us to look smart in front of our Queen. When there is enough from the rations, she bakes a cake. There is a new dress. Once a year. It comforts me. The ritual. The pink blanket, the cake, the walks. The phone calls. The phone calls.

And then it happens. A boy, twelve, leaves his family, leaves London. He will do anything to get out of the town. The countryside calls him. He prefers it to the noise and dirt of the city. The Blitz, 1940s London — eight long months of smog and hunger; who can blame him for wanting more than broken London?

His sisters, all three of them, his mother, his father, all cannot convince him to stay. He is the only son. A son. Boys are worth more. The schools know that the boys want adventure. They make it easy for recruiters to sneak into schools. Mother is upset. But he still cares. He still writes.

But the country, in war times, takes ownership of boys. The men away at war, the boys are needed to work the land. Where is the comfort when my brother is gone? Who will make sure that my head never touches the ground? There is always the dress, the pink blanket but the phone call is a knife. Its ring means Mother’s hope, gone. She begs him ‘Don’t go’. But it’s no use. Mother gives in. Eventually. Signs the consent form. Scared if she doesn’t, he will just run away? No more school. He is supposed to stay til fourteen. What of his education?

Perhaps working-class boys don’t need one. ‘Let him learn to work’— I bet that’s what the country thought. Letters come. Thank God. Mother begs him ‘come back’. It is four years before he does. Why would he? The farm family has no children. They want him. The farmers ask Mother ‘Can we adopt him? We can give you money. ‘’No! That’s my son, he is still my boy.’