by Hannah Arnaud

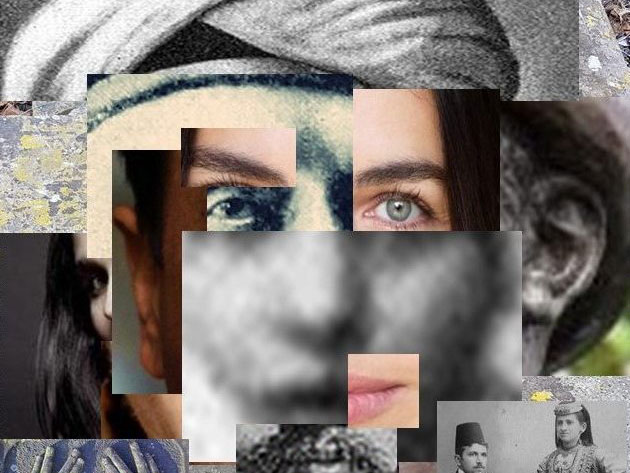

Click onto the One Lost Stone website, a ‘digital travel guide’ to the history of Sephardi Jews in England, and you are brought to a collage of photographs suggesting a face. Although the fragments share a colour palette, the image fractures. Its refusal to meld into one coherent picture is why collage is a particularly apt medium for the website’s aesthetic. It militates against the ‘melting pot’ philosophy which requires the immigrant to adopt the cultural norms of the host society.

Jews did assimilate. Many disappeared into English Christianity or left their faith. Others remained as a tiny Sephardi English society connected to Bevis Marks and its satellites synagogues. We witness this marriage of Jewish and English societies in the photographs and paintings of Jewish men wearing top hats in imitation of upper class English Christians. Indeed, One Lost Stone’s collage reveals the tension between the original immigrants’ Iberian past and the pull of the host culture. The result is a sense of dislocation. This visual fragmentation reflects an uncomfortable sense of being different, an experience common to many Jews no matter how assimilated. It is also common to the one of the other Jewish subgroups: the Ashkenazim from Eastern Europe.

This is my family background and my experience. I explored One Lost Stone’s website, sitting in a cafe in a Jewish area of London. On the walls were paintings by a Jewish artist friend. I had just had my second anti-Covid vaccination in a Jewish cultural centre with mezuzot on the door posts. I was a Jew in a safe Jewish setting. As a third generation Holocaust survivor, in some ways I live a life which proclaims the success of Jewish immigration. And yet, being in that café, and listening to the words of the 1492 Alhambra Decree ordering Jewish expulsion from Spain, and the trial of Leonora Nunes, who was accused of keeping the ‘fast of Kippur’ during the Inquisition, (https://www.lostjews.org.uk/oneloststone/history/persecution-inquisition-expulsion/) I was acutely aware of the ways in which my Jewish heritage and practice estranges me from British society. This Sephardi story of displacement still resounds and One Lost Stone is a testament to that.

The website is divided into sections each focussing on different periods and themes in Sephardi history. Individual pages contain a commentary accompanied by audio clips dramatising stories, poems, and contemporary documents.

There are tales of men who suppressed their Jewish identities and rose to become important in English history. Portuguese Jew, pretending to be a Christian, Dr Roderigo Lopez, physician-in-chief to Elizabeth I was hanged, drawn and quartered after being wrongly accused of poisoning the queen. The struggle for equality in a climate of English antisemitism in the 18th and 19th centuries is revealed on the page Merging Identities (https://www.lostjews.org.uk/oneloststone/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Summary-Merging-identities-28.6.mp3). Did Jewish emancipation depend on conversion? Benjamin Disraeli, whose parents converted to Christianity, became Queen Victoria’s Prime Minister. On the page of Gender & Identity The Missing Women (https://www.lostjews.org.uk/oneloststone/history/gender-identity-untold-stories) we read of extraordinary figures including Emilia Bassano, daughter of a Venetian Jewish musician in the English court. Her father Baptiste had his children baptised in London. She was the first English woman to identify herself as a professional poet. In 1611, Bassano wrote Eve’s Apology in Defense of Women which counters the pervasive, largely Christian interpretation of the Garden of Eden narrative which damns Eve and all womankind.

Yet Men will boast of Knowledge, which he took

From Eve’s fair hand, as from a learned Book.

The name Emilia Bassano was unknown to me even though this text seemed familiar. As a student of Renaissance literature, I was sure I would have remembered a female Jewish poet who unpicked patriarchal readings of the Genesis story. Searching through undergraduate lecture notes I found her in a handout about female devotional poetry. She was hidden under her married name of Lanier. The idea that the lecturer thought it irrelevant to mention Bassano-Lanier’s Marrano identity, while discussing how her poetry subverts 17th century traditional religious narratives, is an erasure of Jewish identity and culture.

However, there was something redemptive in One Lost Stone. It is a place where Jewish stories can be told without embarrassment and without self- justification. It challenges the negation of Jewish life in European history.This is not to be taken for granted. I remember approaching the Dean of my university college at university about running a Holocaust Memorial Day event and being told that ‘No one will come’. He was wrong, people did and the event exemplified the power of sharing stories, music and art together as Jews and non-Jews.

One Lost Stone is doing the same work and I hope you will prove my Dean wrong by visiting the website: reading the stories, seeing the artwork and taking a few moments to reckon with the complicated and almost forgotten history of Sephardi immigration to England.

Hannah Arnaud has just spent a year working for Noam, a Jewish youth movement. She is about to start a Masters degree in Shakespeare Studies at the same time as teaching at her local synagogue. She is delighted to be working with the Pascal Theatre Company, bringing together her love of both Judaism and drama.